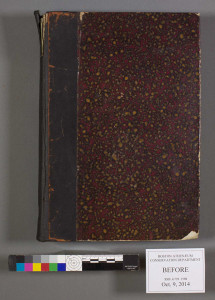

I have been thinking about a recent treatment I did on An Historical Collection of the Most Memorable Accidents, and Tragical Massacres of France quite a bit lately. More than the mere drama of the process, I was really taken by the experience of nixing some old assumptions of mine. Conservation is a relatively new science, and while we work on preserving artifacts that are hundreds of years old, we really only have a few decades worth of treatments and methods to study and improve. There are ways of simulating the aging process in a lab, but nothing is as affirming as standing the true test of time. But until enough time passes, and those ahead of us can OK our treatments (or kick them to the curb, liquid leather I’m looking at you!) we have little more to go on than our assumptions, scientific or otherwise. It is therefore important to revisit these assumptions often, and to feel confident and comfortable in them.

First Assumption: There is little to be done to a sad, sewn, dirty text block.

Conserving a book not only means stabilizing it structurally, but preserving its history as well. To cut sewing is to severe a tie with a bookbinder of the past, and to alter the character of the book and its future. Even when the sewing is replicated exactly, we loose a piece of the history that we are striving to hold onto. Also, this particular book was rather large, and cutting the sewing just to wash and resew it was not an ideal way to spend the week.

Second Assumption: If the text block seems solid, and there are no apparent breaks, the sewing must be perfectly intact.

Three generations of book conservators looked at this text block and confidently assumed, based on their collective experiences and knowledge, that this book was over sewn and intact. One of the most beautiful aspects of working with Special Collections is the craftsmanship that goes into every piece – you can survey hundreds of books bound in the same tradition, but every one of them will reflect quirks of their individual binder(s). You can never be certain that a mistake wasn’t made somewhere in the process, that a new technique wasn’t being developed, or that a specific structure was ever intended to fully mimic another. We can make generalizations and assumptions about collections, but we really must treat each object as its own.

This particular book I was working on was printed in 1598, and the paper is just stunning. However, after 400 years anyone would have a few cobwebs to clean out, and it was discussed that a good wash would have really done it some good.

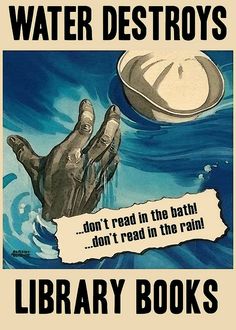

Third Assumption: You cannot wash a whole book.

For the most part, paper and water are actually good friends, especially when introduced in a controlled manner. And while Cellulose and H20 may go way back, the thought of a soggy book remains horrifying. I have always assumed, as perhaps the above poster brainwashed me into thinking, that it should be avoided at all costs. However, this assumption of mine was quickly dismissed when washing the text block in its entirety was suggested. With a quick search of the CoOl archives, Bill Minter‘s description of this very idea popped up. As he mentions, this treatment is rarely prudent, but just because the right opportunity doesn’t present itself often doesn’t mean it isn’t a possibility to consider.

In any science, especially when one is new to the field, it is easy to assume that the methods you were taught are the only methods that should be employed. But stopping once in a while to question and consider your techniques, especially the most simple, is important. Why is paste sticky? What amount of abrasion does a latex sponge cause? What parts am I actually trying to put back together? For me, washing an entire book was so out of the ordinary, and such a foreign treatment that I was forced to stop and think about every step along the way. Ideas I had held as truths started to feel less certain – if I put paper in water might it dissolve and turn to pulp?! Will the pages stick together if they’re washed or dried on top of one another? Is there dirt IN the pages? I had never had cause to consider such things when I washed a book in leaves; I was taught this was an appropriate method, and that I could expect certain outcomes in certain situations. Of course I knew that every book was different, and that spot testing was important, but I didn’t ask why A always equaled B, or pondered the possibility of irrational results. When we assume something is tried and true, we don’t feel the pressing need to think about it actively. I took it on blind faith.

But we went ahead with Bill’s directions anyway- we set up a “fish tank”, had our interleaving ready, and our wind tunnel built.

I took a deep breath, and lowered the oldest book I have ever worked on into what I assumed could easily be its watery grave. But, science held out and the paper reacted just as it would have in sheets. I was not left with a 5 gallon bucket of paper slush.

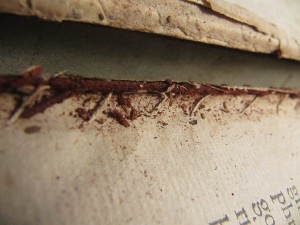

However, we did discover that the sewing wasn’t actually intact. The first few sections had been over sewn, but the rest were held together only by the remnants of sewing and adhesive. Sections started sloughing off as the water developed that satisfying ocher.

Fourth Assumption: Assume the book is intact, and continue with the experiment anyway.

We carried out the rest of Bill’s methods with the sections stacked together as a single textblock.  We were all curious to see how the book would dry, and how the paper would respond to a week long stint in the Motel 8 of wind tunnels. Continuing in this manner gave me time to consider and investigate the methods of washing, drying, and flattening that I had learned. And although it turns out that washing and drying intact is not actually faster, it is still just one more possibility.

We were all curious to see how the book would dry, and how the paper would respond to a week long stint in the Motel 8 of wind tunnels. Continuing in this manner gave me time to consider and investigate the methods of washing, drying, and flattening that I had learned. And although it turns out that washing and drying intact is not actually faster, it is still just one more possibility.

All in all, this book was just rife with learning opportunities…

Fifth Assumption: If you find you’ve sewn a section in upside down, you must take the book apart and start again (even if you’ve already laced your boards on).

After deciding that this assumption was NOT the direction I wanted to go in, I took a step back from the project and considered it from every angle I could muster. We decided that if I cut the sewing (gasp!) around the incorrect section, I could then turn it about and resew it through the newly lined spine. This was not an ideal situation, but it was an opportunity to think about the book structure, and all the implications of altering it.

Sixth Assumption: Once you’ve covered a book in full leather, and it has dried overnight, you do not get any more redo’s.

Yet another learning opportunity! I had covered this book the first time in a skin that made everyone in the lab raise an eyebrow. It was a very strange shape, and looked a bit wonky. However, we assumed it would come out just fine in the wash. Never had I been so disappointed to come into work the next morning. The leather was puckered and wrinkled in all the wrong ways, and simply did not seem salvageable. Perhaps there were design opportunities in this glaring mistake as a bookbinder, but as a conservator, there was nothing to be done.

However, paste is reversible. Duh. And there were plenty of new skins to choose from. So after much debate and inner conflict, I decided to test just how reversible it was. Again, not an ideal situation, but I was able to remoisten the leather and lift it off its new boards. It was certainly a set back, but not nearly as detrimental as I had first thought it to be. With a little bit of sanding, and a new paper lining, the boards were fit to be covered.

Again.

But, after much preparation, research, collaboration, and thinking outside of the box, I was somehow able to take this book from drab to fab, and to reassess my ways of thinking in the process.

Thanks so much for posting this! I took Renate Mesmer’s class a few years ago and have been asked to demonstrate vertical text block washing at the Duke Library Lab. It has been hard to find information about this treatment and your post is very helpful. It would be great if you could reply to me via email at Mary.Yordy@duke.edu.

I am finding that the ‘throw away’ 20th Century books I have to experiment on are really not behaving as expected in the bath. They seem inclined to float and refuse to fan open as yours did, and as the ones in Renate’s workshop seemed to naturally do. I think it may be a quality of this pulpier, coarser paper of the 1930-40 era. (This was after spraying throughout with a solution of water and alcohol.) The other issue I had was drying. The books, even with the wind tunnel, have not dried quickly enough to prevent them from developing mold, etc. Somehow Renate’s book was dry the next morning.

Hi, could you please give me credit for my creative-commons licensed image? You’re welcome to use it, but credit me please. Thanks! Here is the original source of the image: https://www.flickr.com/photos/suzypictures/3424038332/in/set-72157617442676617