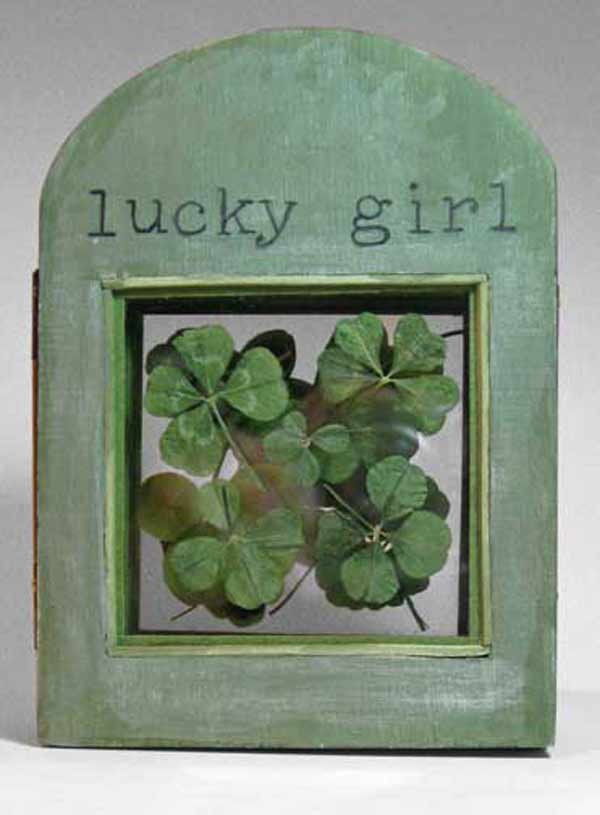

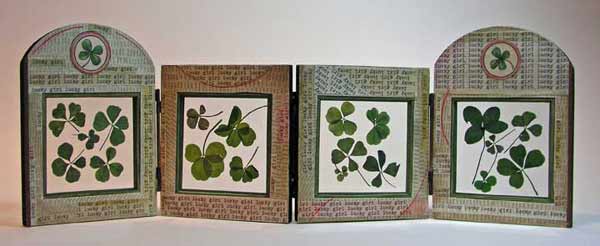

One of my favorite books from Laura Davidson is Lucky Girl. This unique accordion book bound with handmade hinges is inspired by Laura’s daughter, who can spot a four-leaf clover anywhere. Clovers from Michela’s collection have been delicately sandwiched between glass in each wooden page, which is also collaged with the typed text “lucky girl”.

Since 2010, the vibrant green clovers have dried out and aged to a yellow-brown. During my visit, Laura brought out a book from her library. Tucked inside was a surprising collection of four-leaf clovers, each marked with the location where they were plucked.