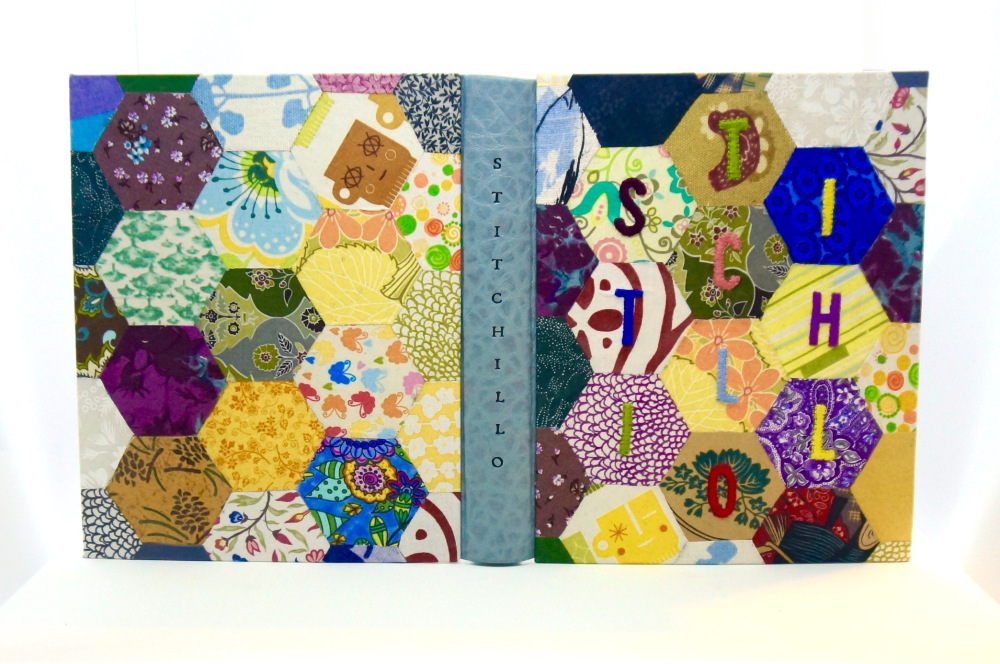

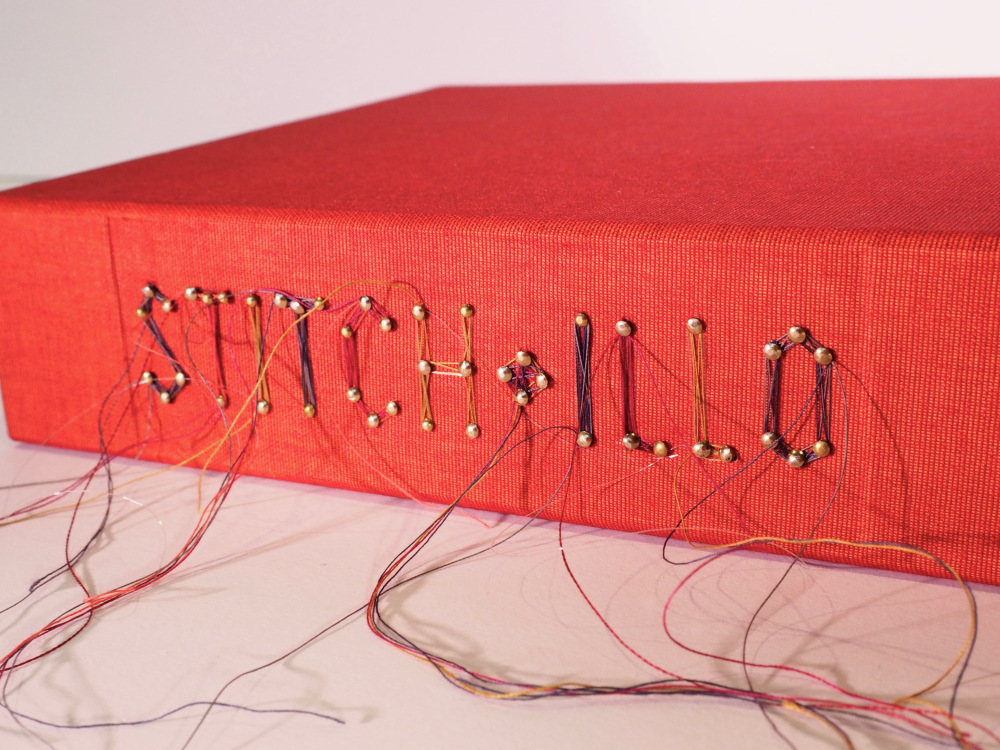

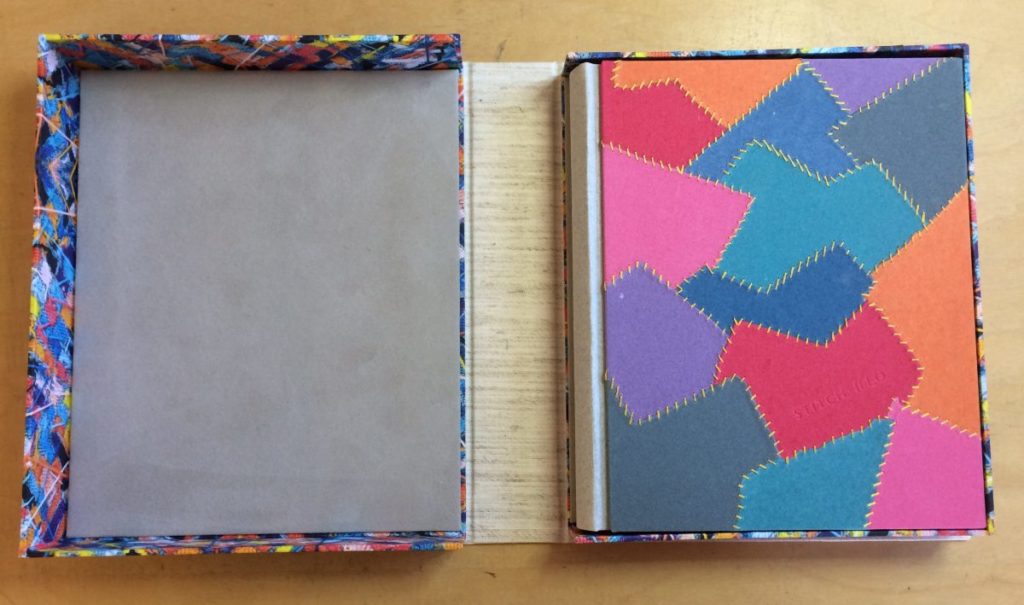

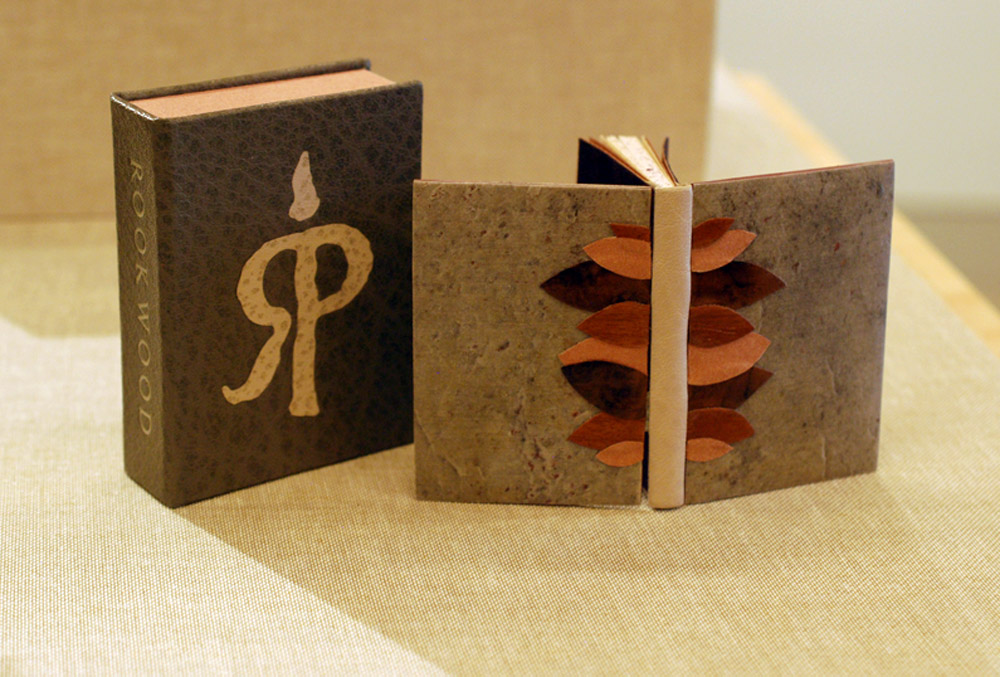

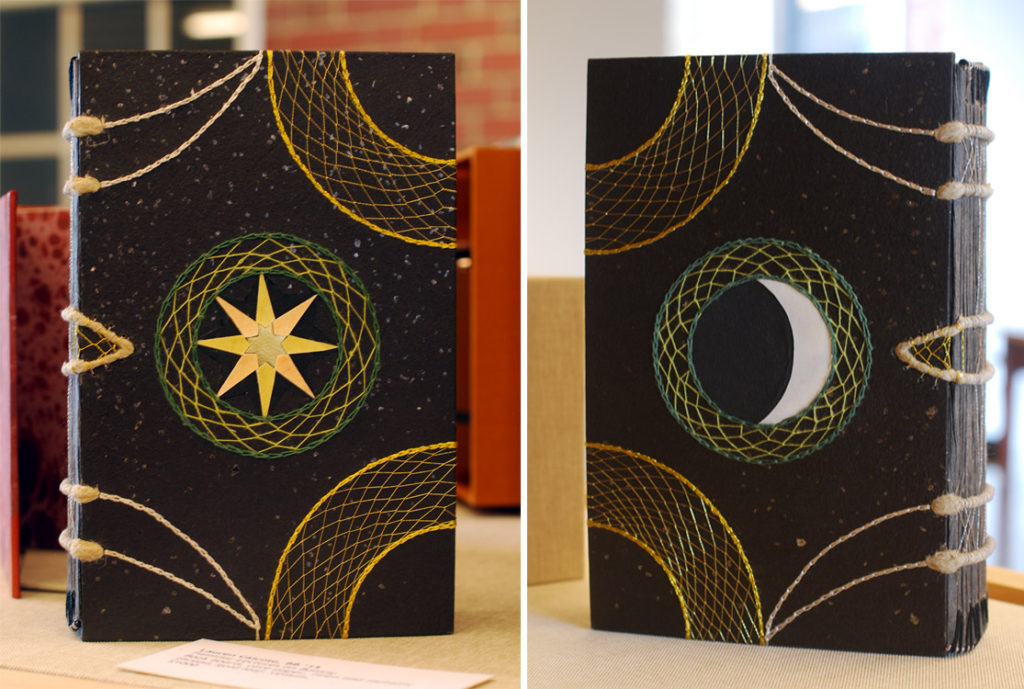

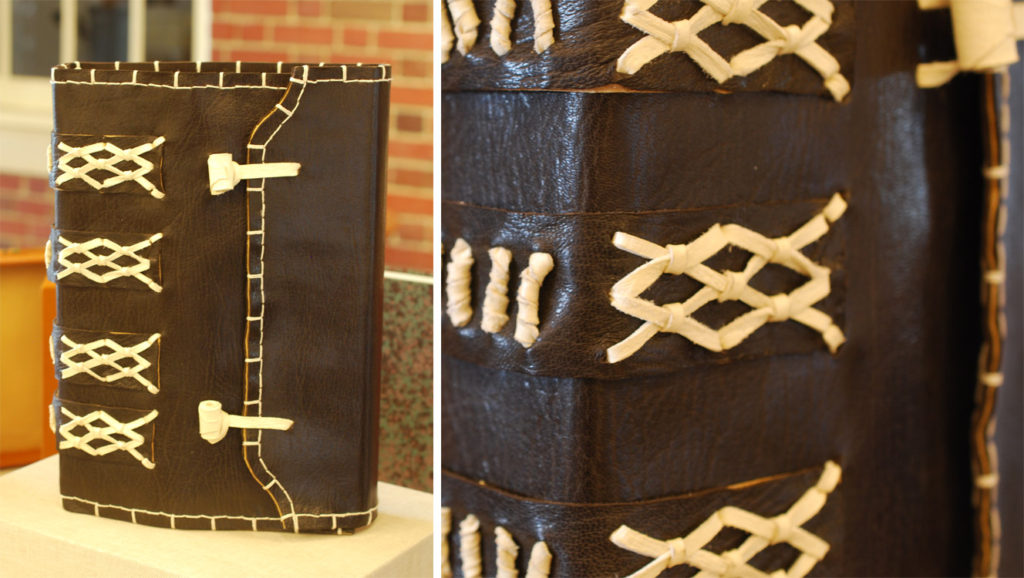

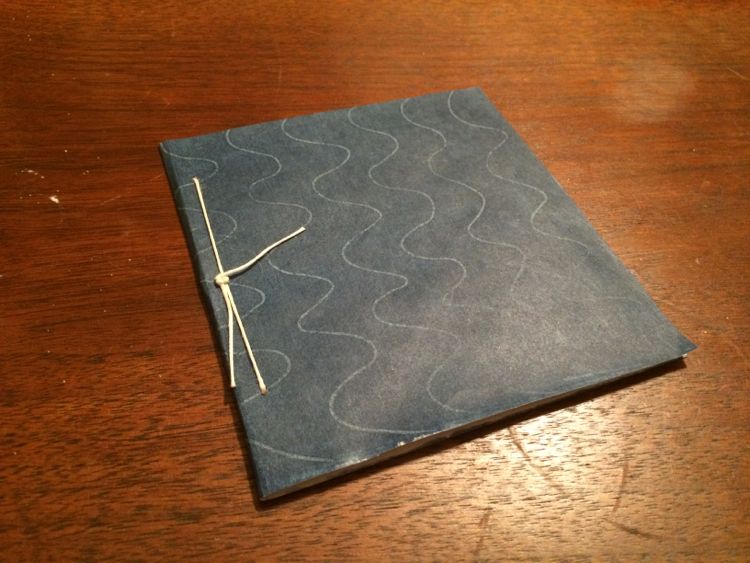

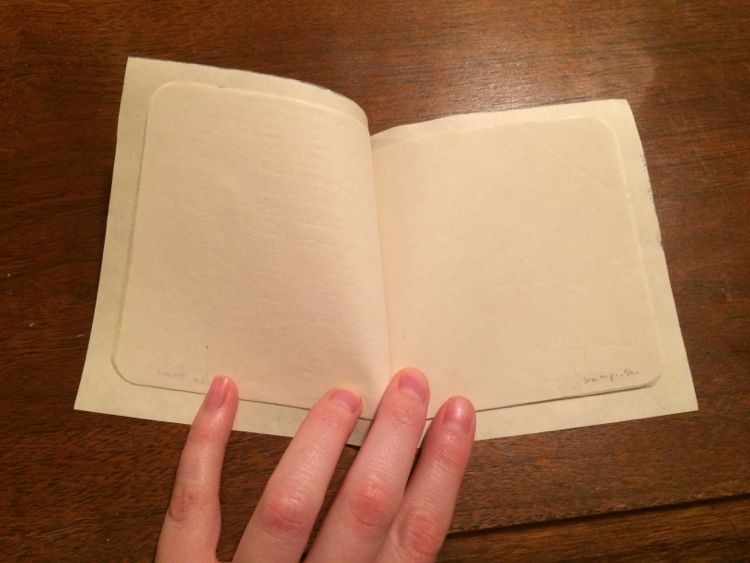

Last year, I posted about my binding Feed Sacks: The Colourful History of a Frugal Fabric, which came about through an invitation from Todd Pattison. Along with fourteen other binders, we each bound a copy in our own style. The Feed Sacks bindings are now on display at the Iowa Quilt Museum alongside objects made with feed sack fabrics. In addition to our bindings, we also had the chance to recommend a binder for a second project. Janine Vanpool, the publisher of Uppercase magazine generously donated copies of Stitch·illo – Creative Expressions through Thread and Fiber.

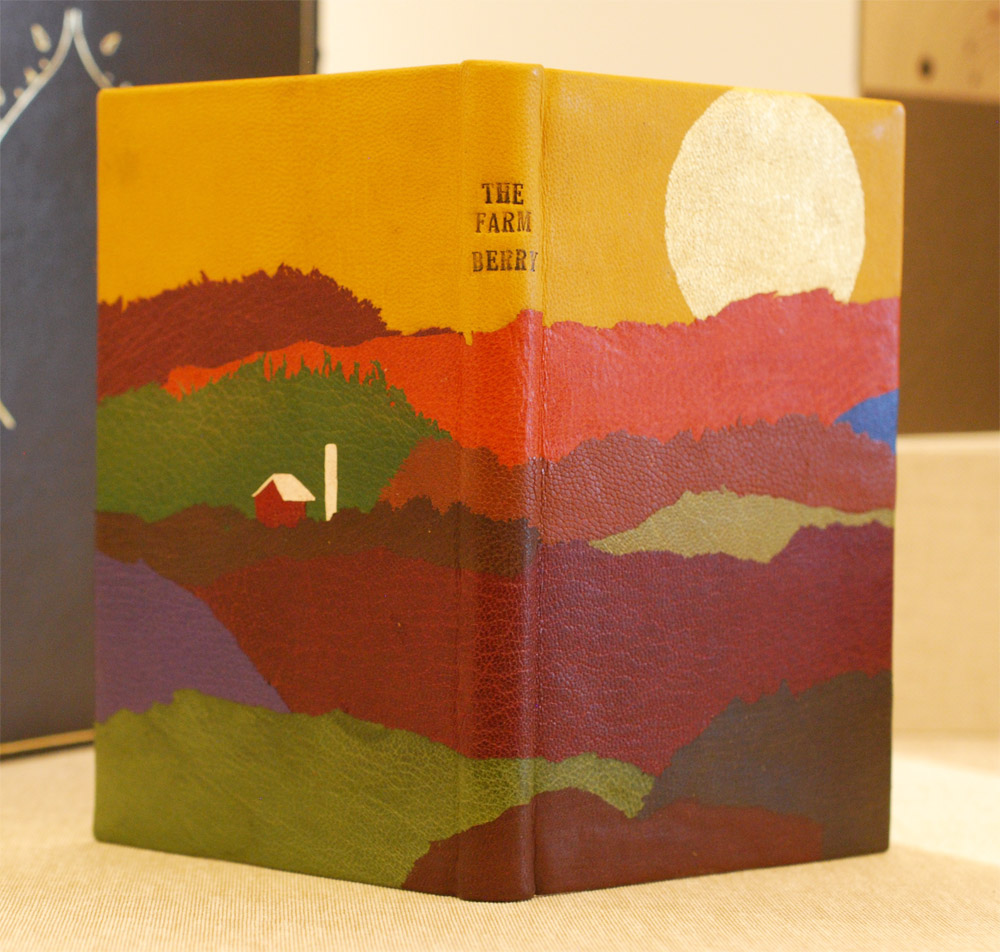

This book profiles 46 contemporary artists who are using embroidery and other textile processes to explore their art by honoring historical techniques and exploring new ways of crafting through fiber arts. Check out the fifteen binders who put their own unique spin on Stitch·illo.