In addition to the set books I wrote about in Part One of this post, the Student and Alumni Exhibit at North Bennet Street School includes a selection of bindings produced by current students and alumni of the full-time program. In this post, I’ll be highlighting some of my favorites.

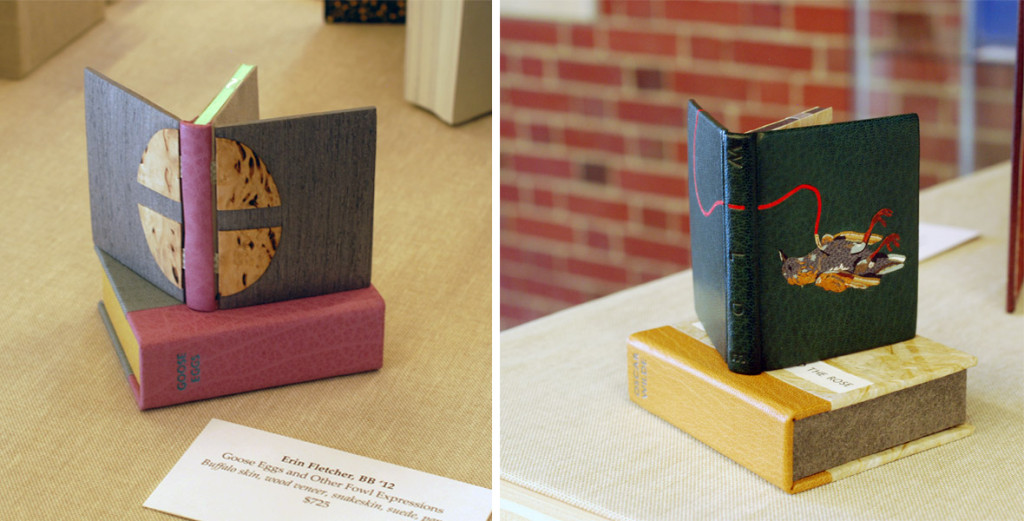

I’ll start with my own bindings. This year I submitted two miniature bindings, which I’ve completed within the last 8 months. The book on the left is Goose Eggs & Other Fowl Expressions bound in the Dorfner-style with wood veneer boards. I wrote about the process a few months ago, you can check that out here.

The second binding is The Nightingale and the Rose by Oscar Wilde. The book is bound as a traditional French-style fine binding. The nightingale on the front board is created using various back-pared onlays, feathered onlays and embroidery. For those of you who know the story, there is also a small wood veneer inlay that represents the rose’s thorn. The binding includes tan goatskin doublures. The back doublure showcases the rose and was created in the same manner as the nightingale.

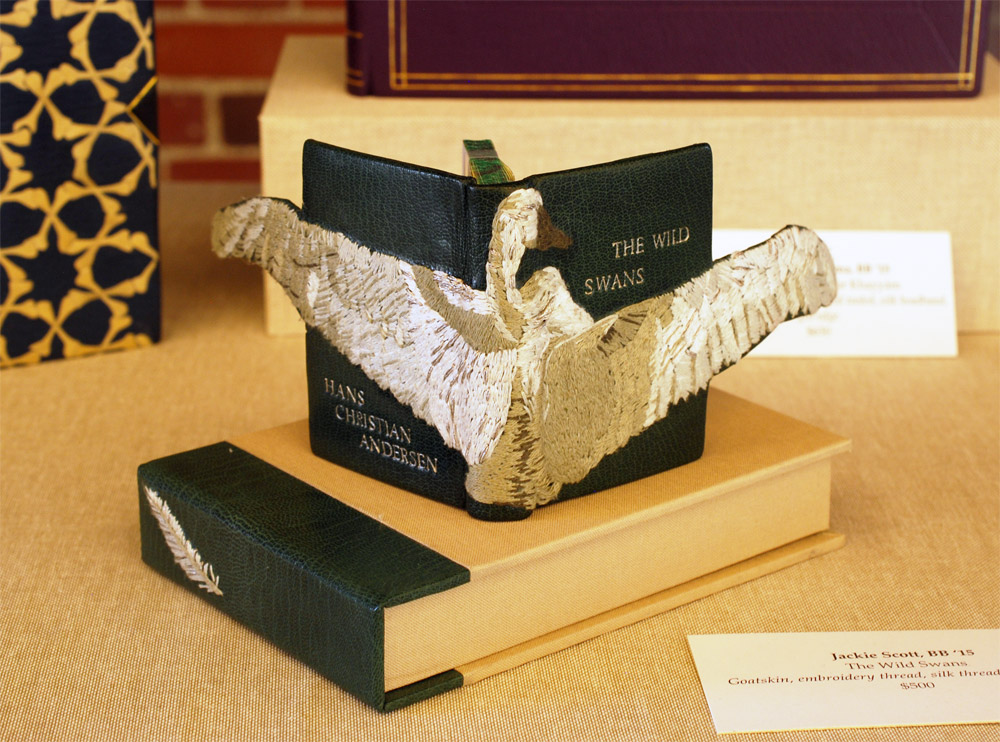

Next up is Jacqueline Scott’s embroidered binding of Hans Christian Andersen’s The Wild Swans. Jacqueline is apart of the 2015 graduating class and I featured her set book in the first post. Her work is so stellar and I had the delightful opportunity to see this book as it took a journey to became this very gorgeous binding.

The embroidery is so delicately handled and the feather embroidered on the spine of the box adds just the perfect amount of intrigue. The swan’s wings extend beyond the fore edge and are covered on the backside with matching green goatskin leather. I can’t wait to see how Jacqueline continues to explore embroidery in her work.

The rest of the images were taken after the exhibit was fully installed, so please pardon any glares, shadows or my reflection. I would also like to note that I had intended to include the work of Rebecca Koch and Anne McLain, but it was rather difficult to capture an accurate photograph of their bindings due to reflection and glare issues. So sorry you two but I would like to say that loved your bindings!

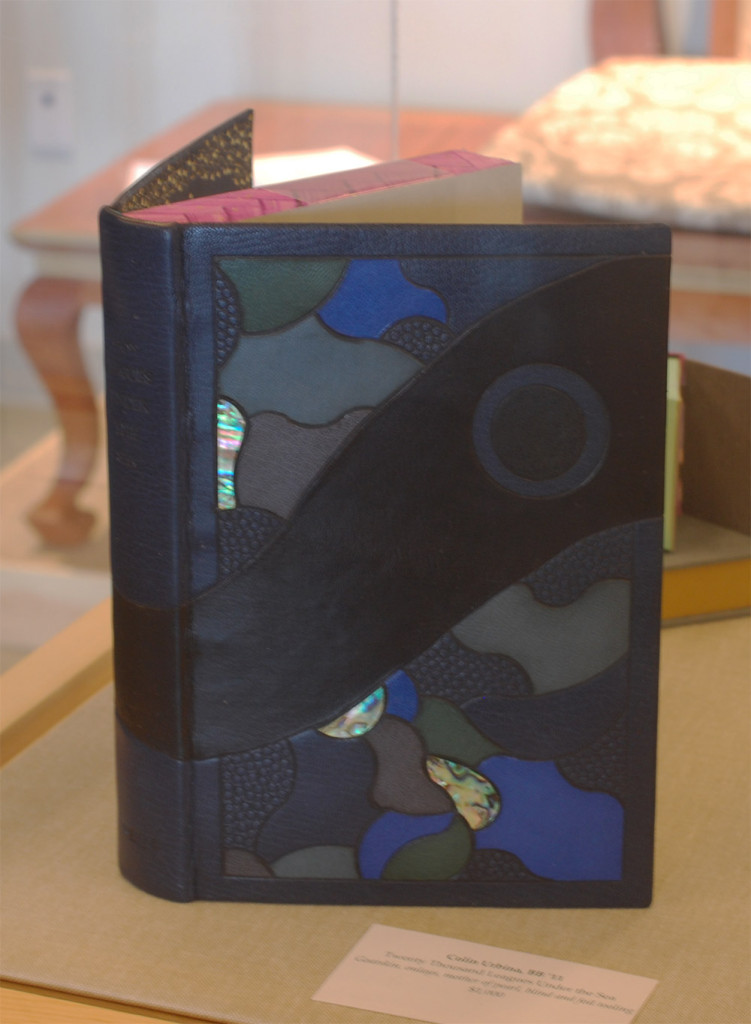

The following binding was recently bound by my charming bindery mate Colin Urbina, 2011. In his binding of Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea by Jules Verne, he created an abstract underwater scene with several tooled leather onlays and inlays of pearl. Other portions of the design are texturized with an open circle tool and by pressing sandpaper into the wet leather. The title and author are blind tooled on the spine.

The head edge is painted in a vibrant purple with brushstrokes that cross over one another. Colin put in matching edge-to-edge doublures and added a frame of ascending “bubbles” using the same open circle tool.

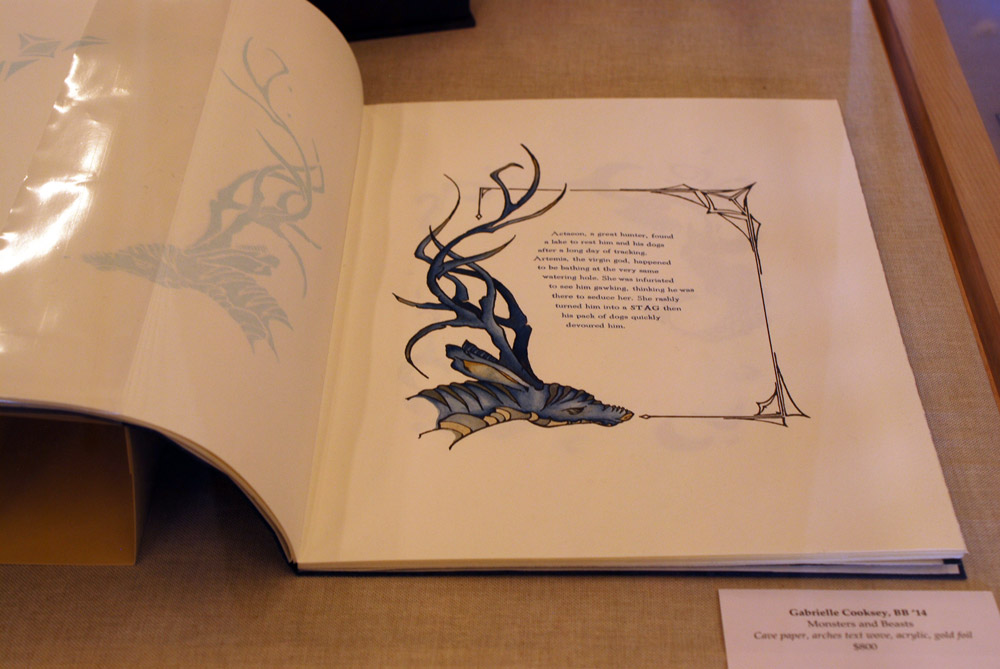

Monsters and Beasts is the work of the incredibly talented Gabrielle Cooksey, 2014. Unfortunately, I don’t know much about this piece. But I believe that everything from the illustrations to the printing were all done by Gabrielle. It’s absolutely beautiful work!

Kaitlin Barber is the master of miniatures (and there always seems to be one in every class). In this adorable and wildly impressive collection of bindings, Kaitlin has miniaturized a selection of historical bindings she learned over the course of her time at North Bennet Street School. She’ll be apart of the 2015 graduating class and I wrote more about her work in the first post.

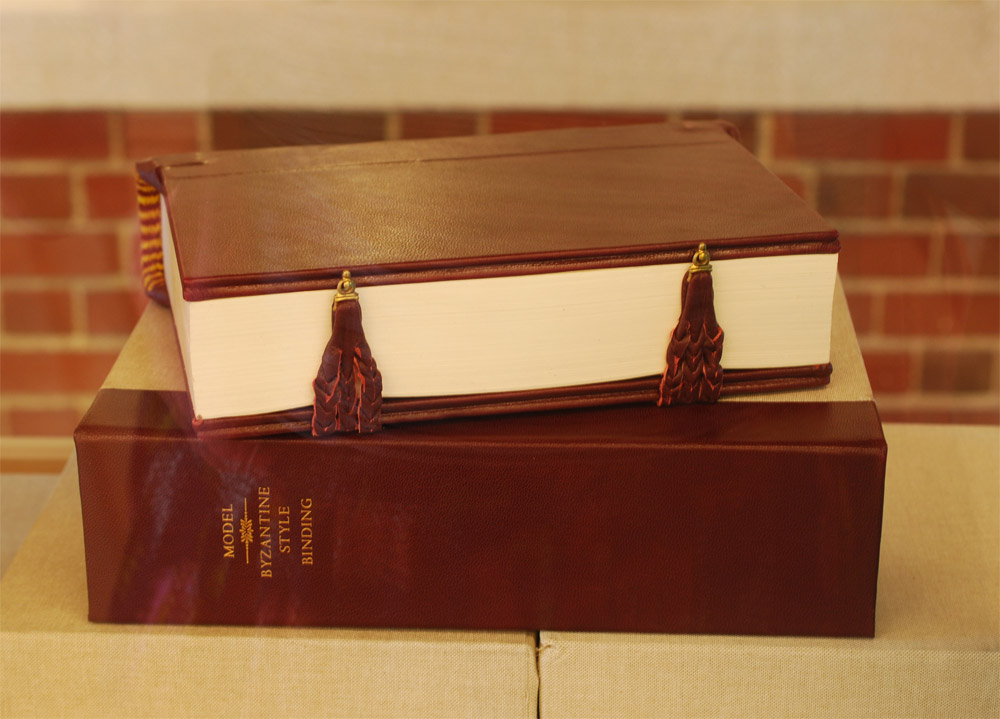

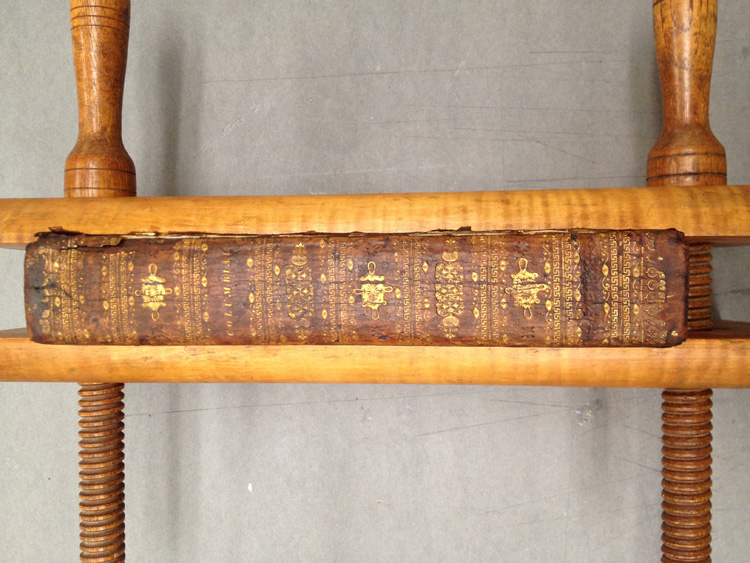

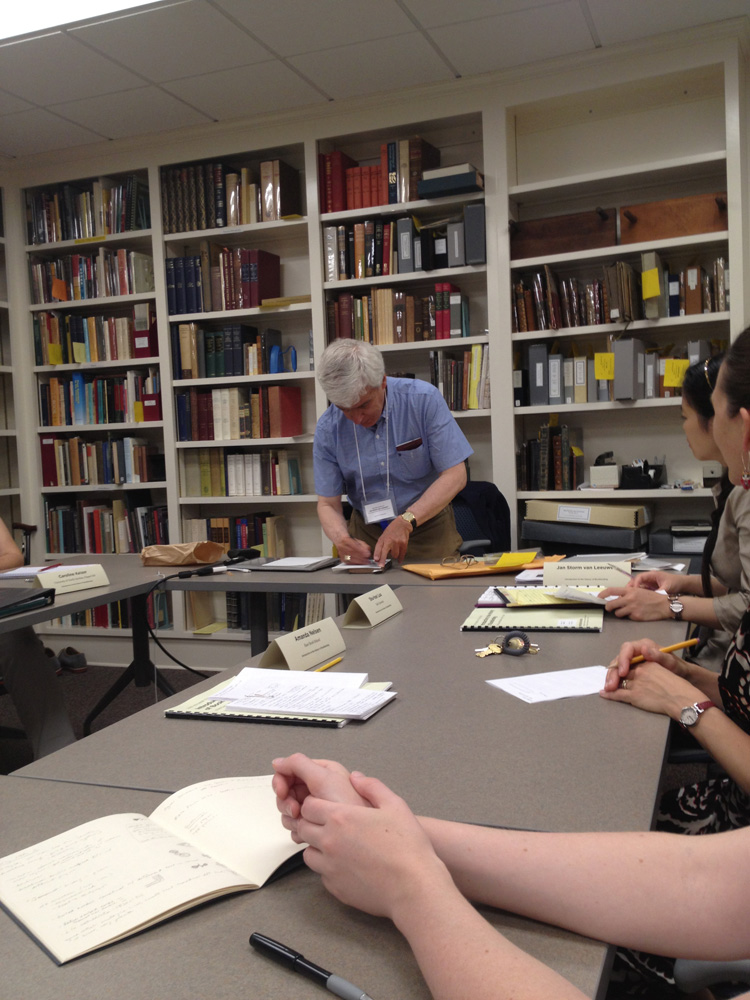

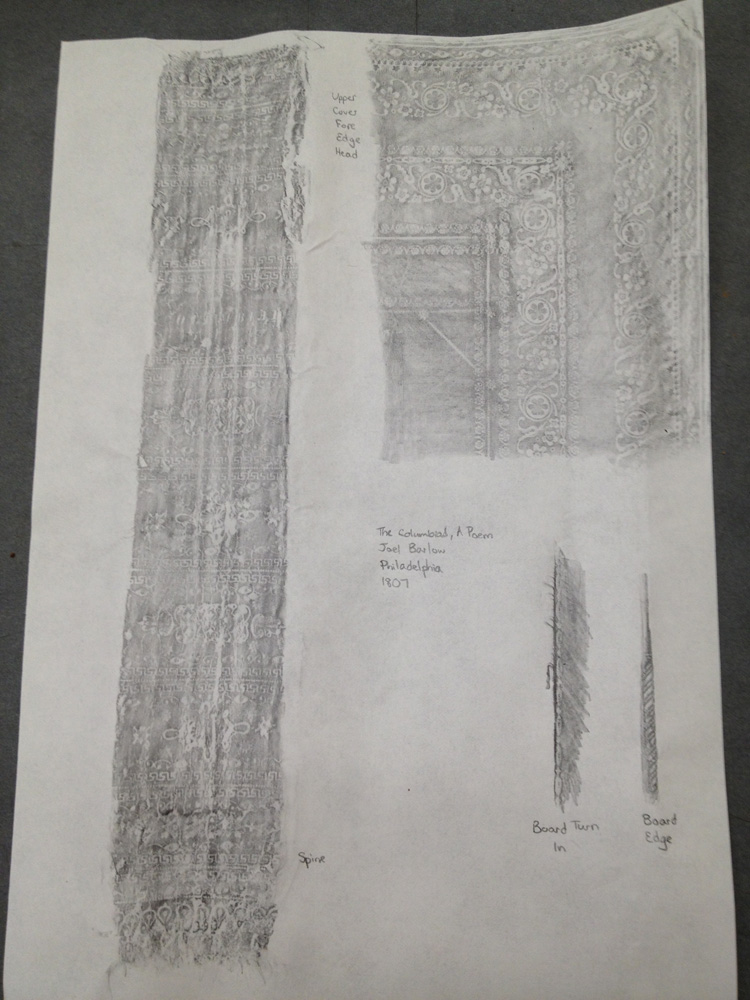

Continuing on with the topic of historical structures, the students were treated to a week long workshop in the spring with Dr. Georgios Boudalis. Using his extensive understanding of Byzantine culture, he taught the students none other than a traditional 12th century Byzantine structure. Todd Davis, 2016, included his binding in the exhibit. The bindings are quite massive and required a lot of detailed work, such as board shaping, primary and secondary headbands, braided straps and clasps. After all that blood, sweat and tears, the class bound some really lovely models.

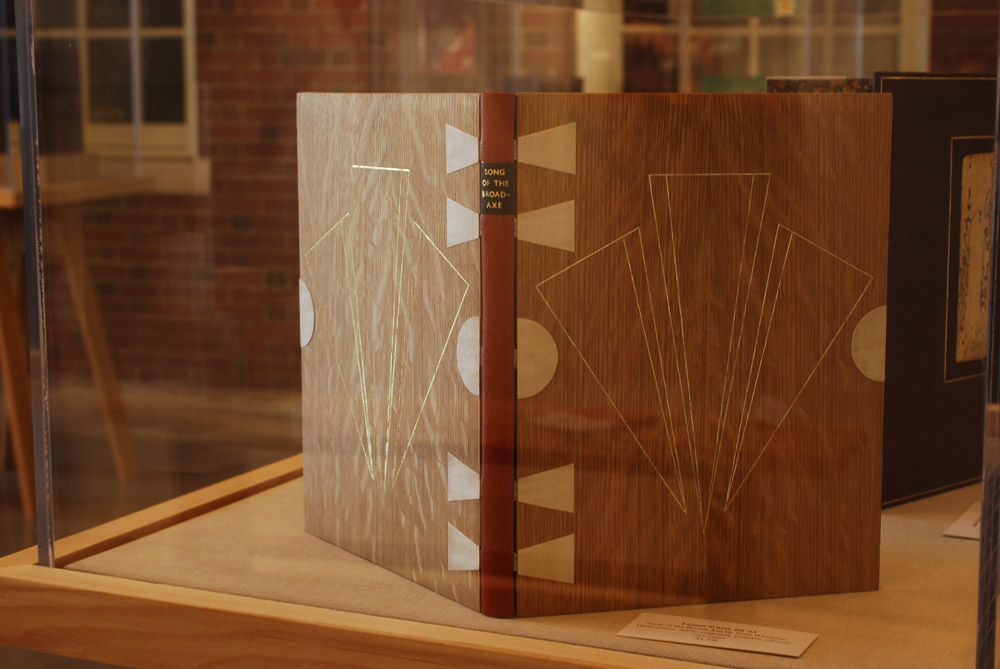

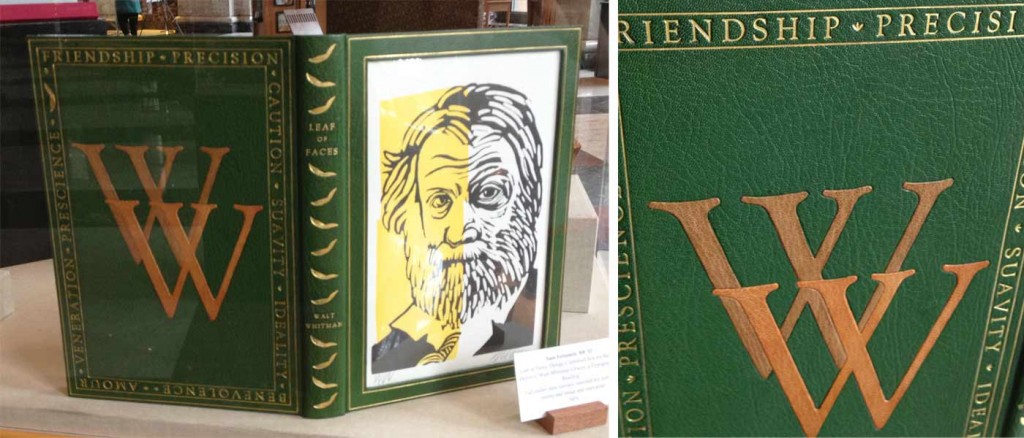

The next binding on my list of favorites was done by another studio mate of mine, Lauren Schott, 2013. Bound in the Dorfner-style (same as Goose Eggs) with wood veneer boards and a leather spine. Lauren’s design on this binding of Walt Whitman’s Song of the Broad-Axe is so elegant.

Lauren and I are both a big fan of incorporating shapes and symmetry into our designs. The front and back board are gold tooled onto the wood veneer; the tooling sits in the veneer so that at certain angles becomes almost invisible.

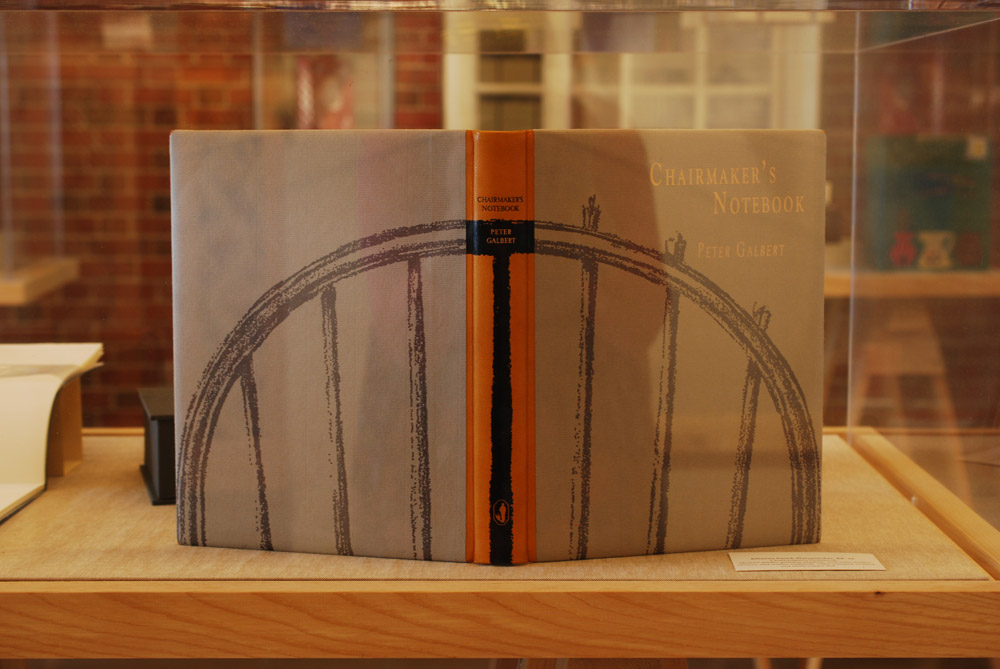

And to round out the favorites is this stunning binding from Johanna Smick Weizenecker, 2010. This binding of Chairmaker’s Notebook is a quarter leather goatskin binding with semi-hidden corners. The design on the front and back cover continues onto the spine as an onlay. The title and author are hand titled using black and copper foils.

So that concludes this year’s Student and Alumni exhibit at the North Bennet Street School. I hope you enjoyed this overview and I want to thank all of you who were able came out to see the show in person!