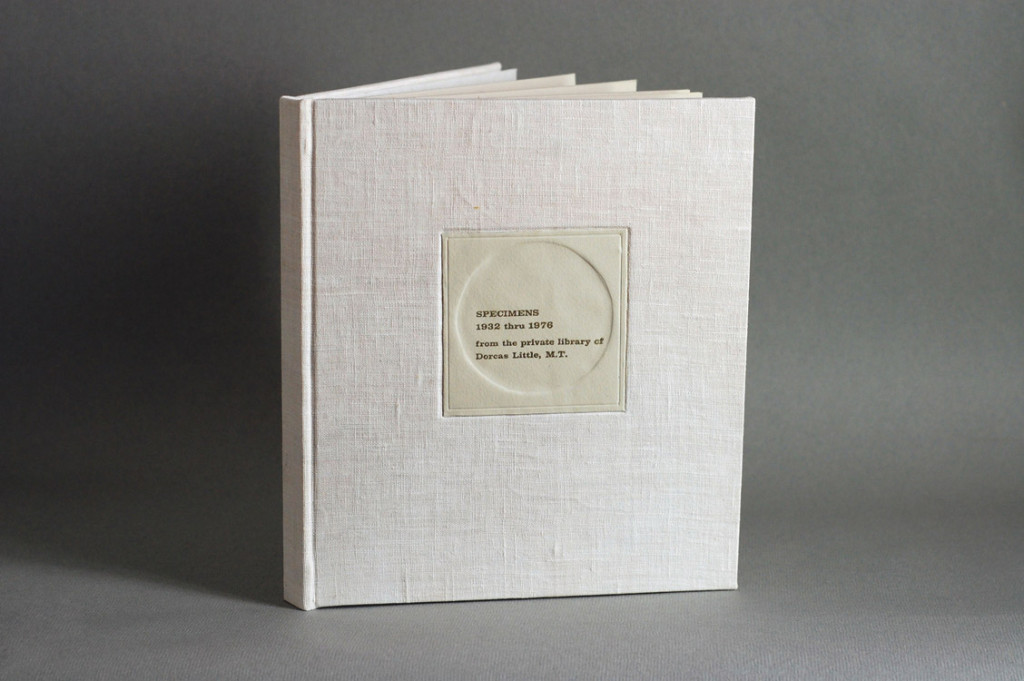

In this final post with Natalie Stopka, we continue the discussion on her techniques that employ natural pigments for dying and image making by looking at her 2012 artist book Botanica.

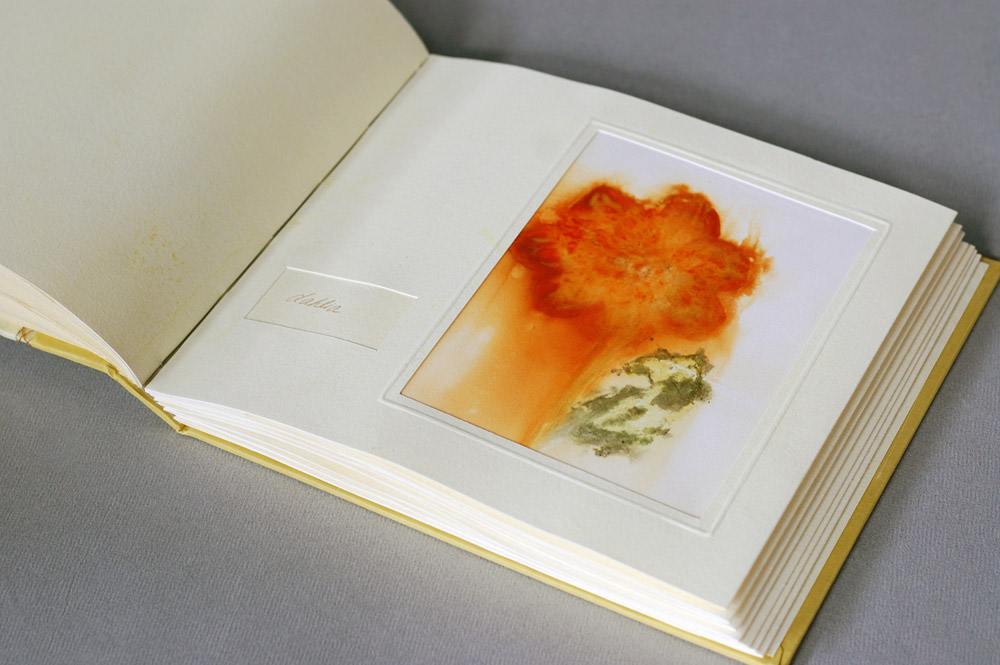

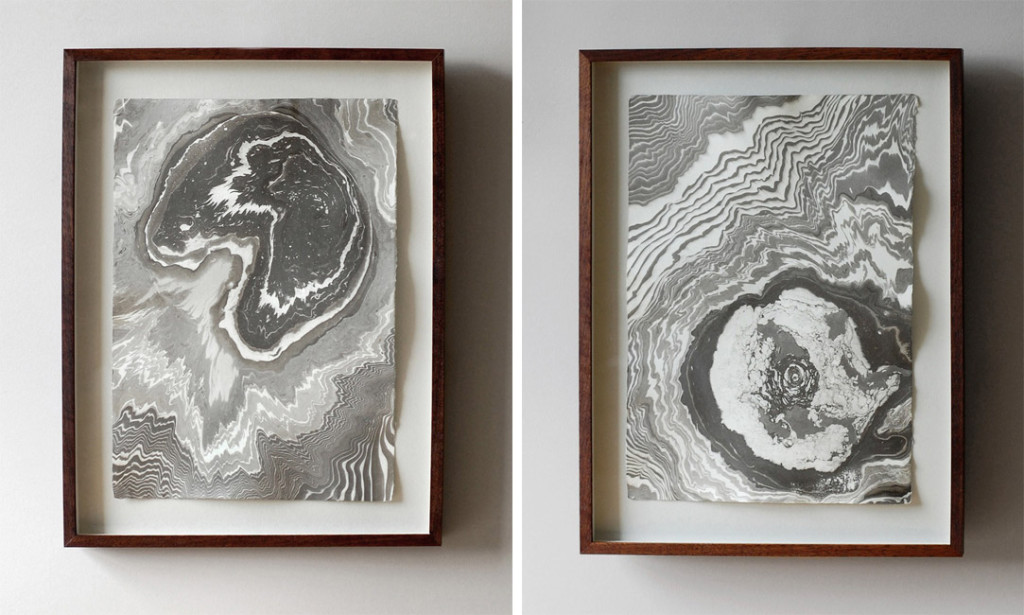

This binding consists of a series of eco-prints that are brilliant in both color and detail. Can you discuss the process behind eco-printing?

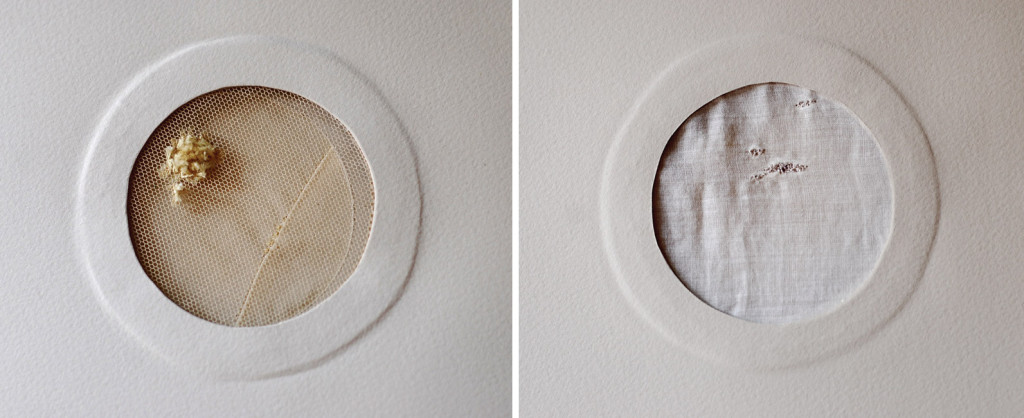

Eco printing is the process of making a plant print using only the natural colorants contained within the plant. As opposed to nature printing in which pigment is applied to the surface of natural objects, in eco printing the plants can be smashed, pressed, bundled, soaked, steamed, or even frozen to coax the dye colorants out. There are a variety of techniques and terms to describe them. Hapa zome is the pounding of fresh plants directly onto a fiber substrate, and bundle dyeing involves tightly wrapping plant or other dye materials in fabric before burying or steaming them.

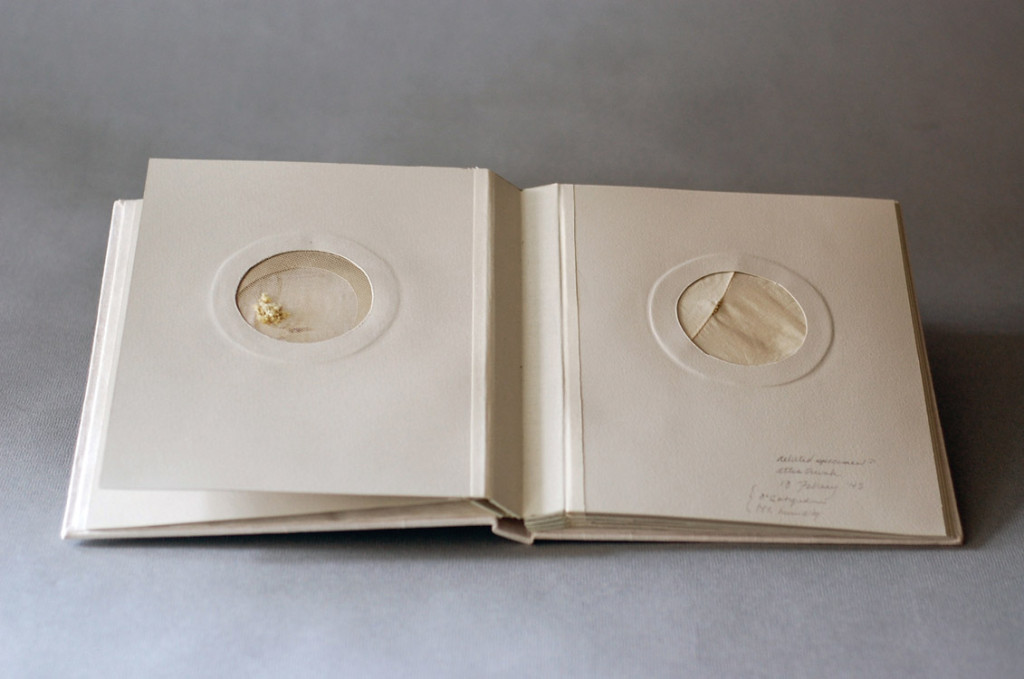

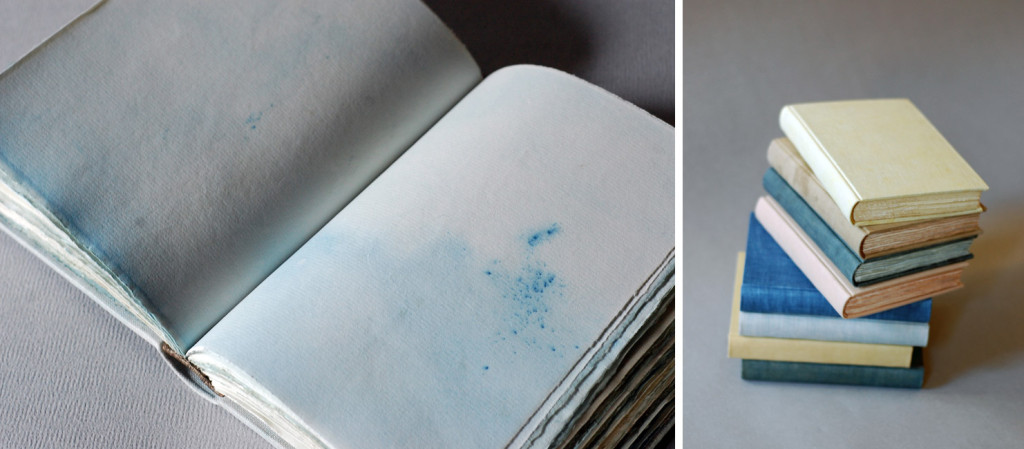

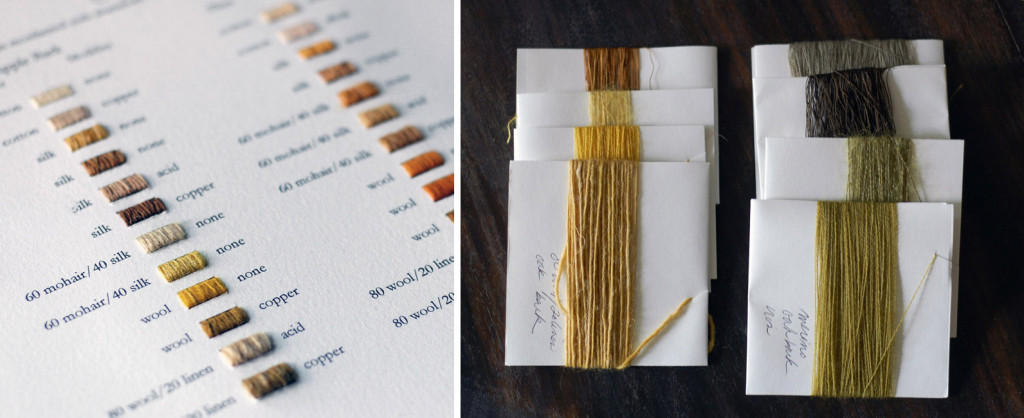

To create Botanica, I gathered a dozen different dye plants one August day. These included mint, yarrow, dahlia, coreopsis, and goldenrod. Each specimen was folded within alum-mordanted paper, guarded with additional paper, and vigorously smashed with a mallet to break down the plant fibers and transfer the colorants within. I lowered this sandwich, with the plant still inside, briefly into a pot of simmering water. The hot water further drew out the dyes, creating an aura of color around the plant image, and made the print as permanent as possible. I was left with two mirrored images of each plant to create an edition of two books.

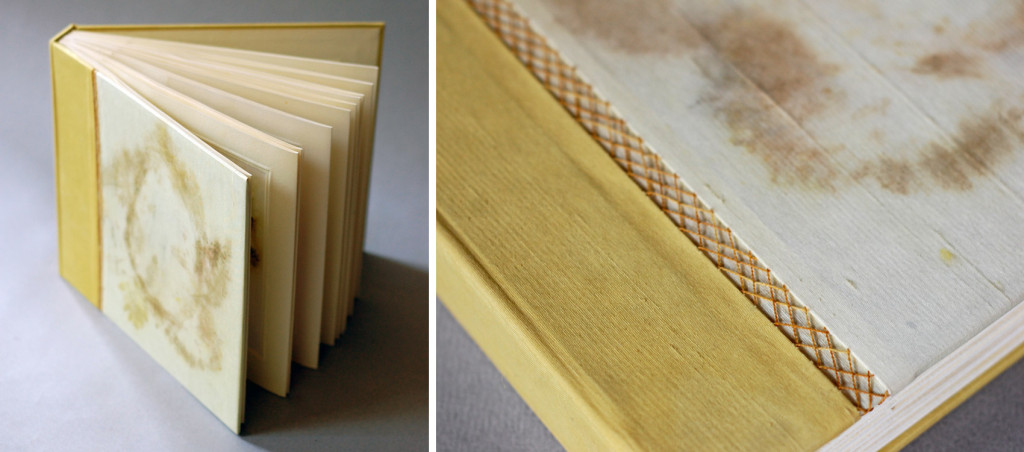

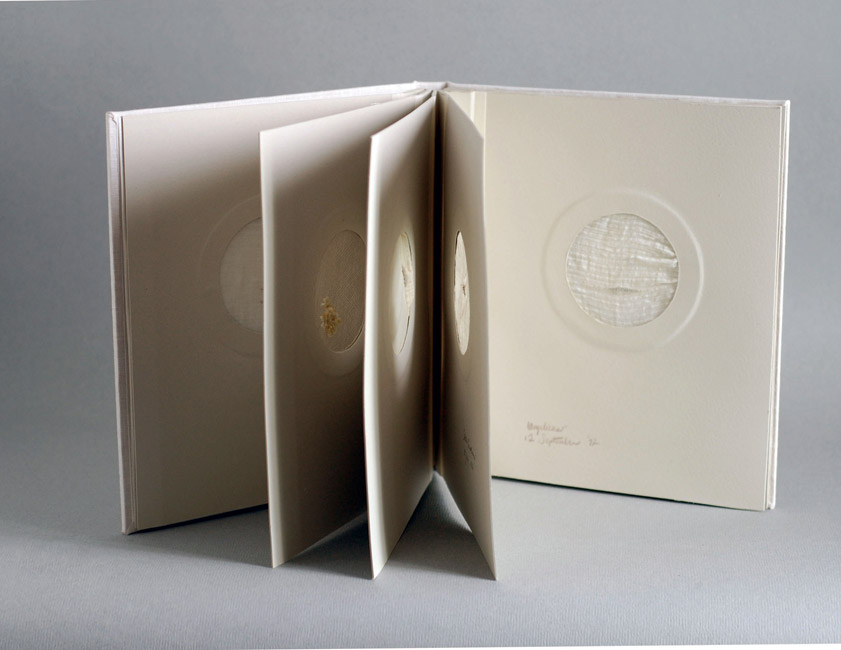

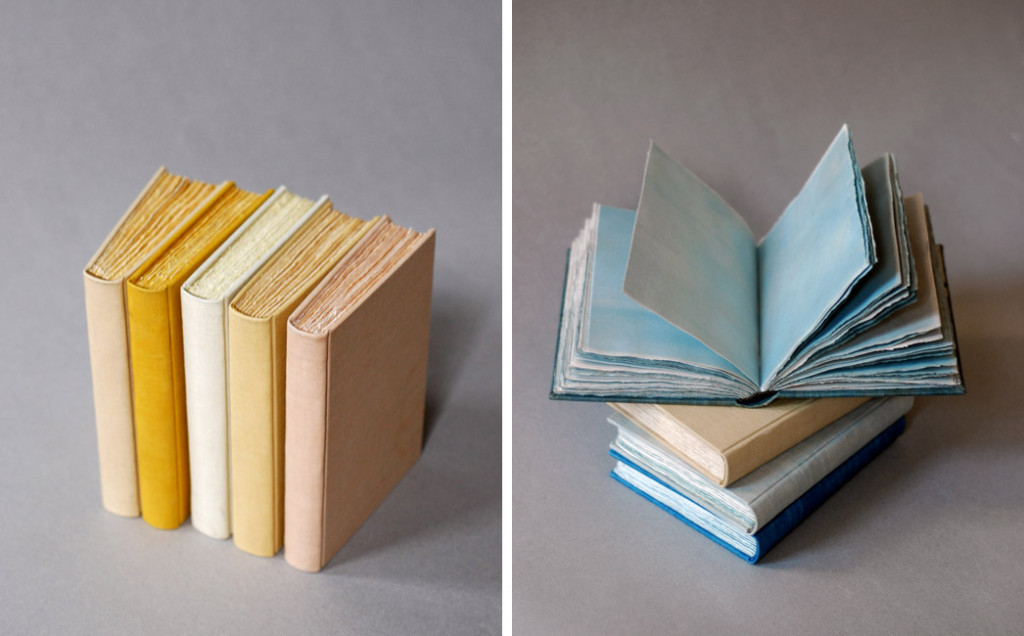

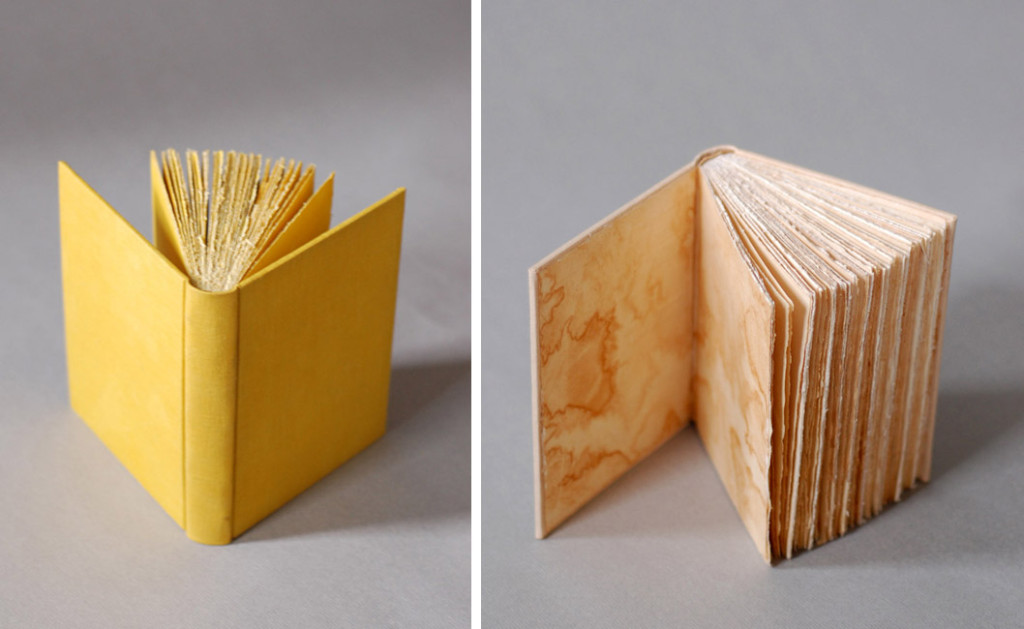

In binding the books I adopted a flat back variation of Richard W. Horton’s light album structure, with each print mounted inside an accordion fold of naturally dyed paper. The paper as well as the silk book cloth and thread on the cover were dyed with a mix of wildflowers.