One of the most important questions we need to ask ourselves as book conservators is how the object we are working on will be used. What is driving the need for treatment? Because there are often so many different treatment paths we can choose from for one object, this question not only helps us to narrow the path of treatment, but it also helps to make sure that we don’t over treat an object, altering something in a way that might be irrelevant to its ultimate use. If we aren’t asking this question before beginning, thoughtless and potentially harmful treatment is most likely to result.

There are three reasons for treatment that I see most often: heavy reader use, exhibition, and digitization. Each presents unique challenges and treatment options . . .

Heavy Reader Use:

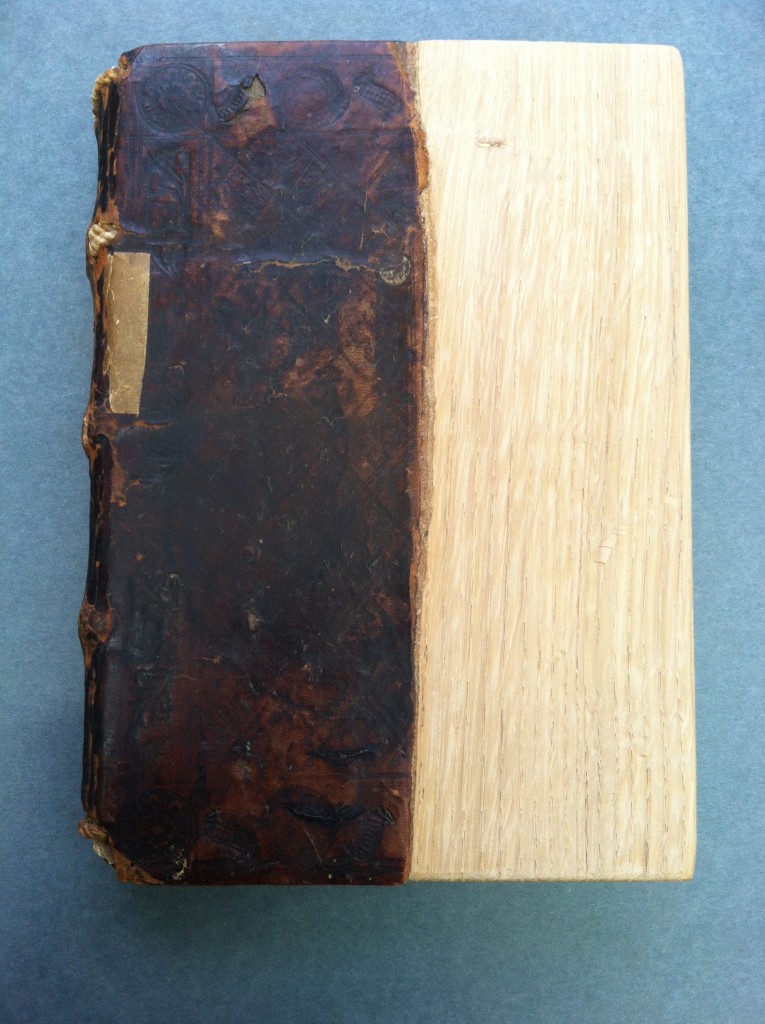

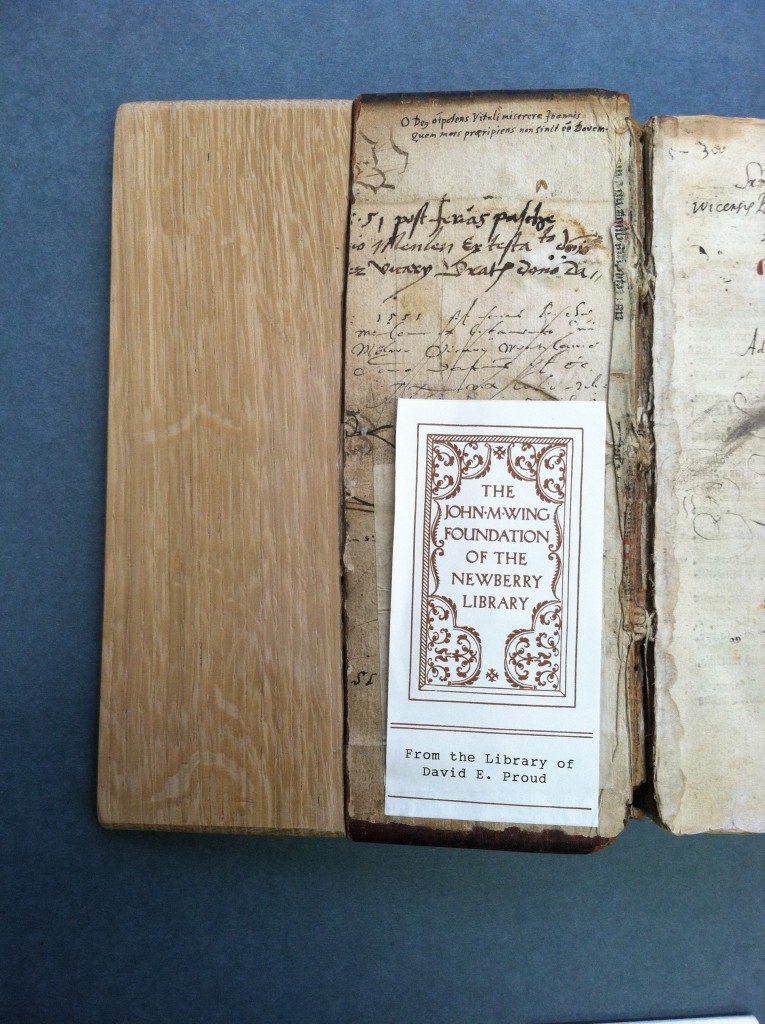

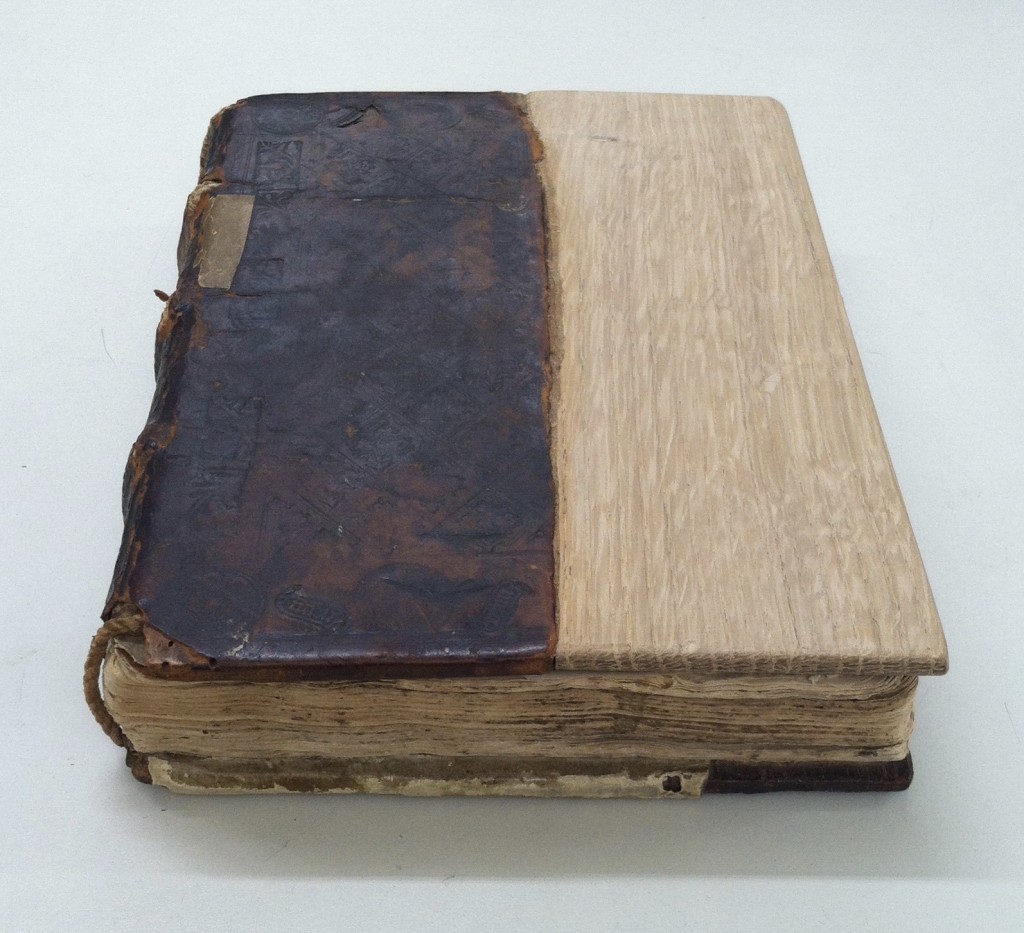

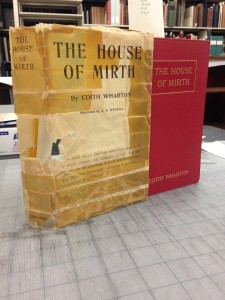

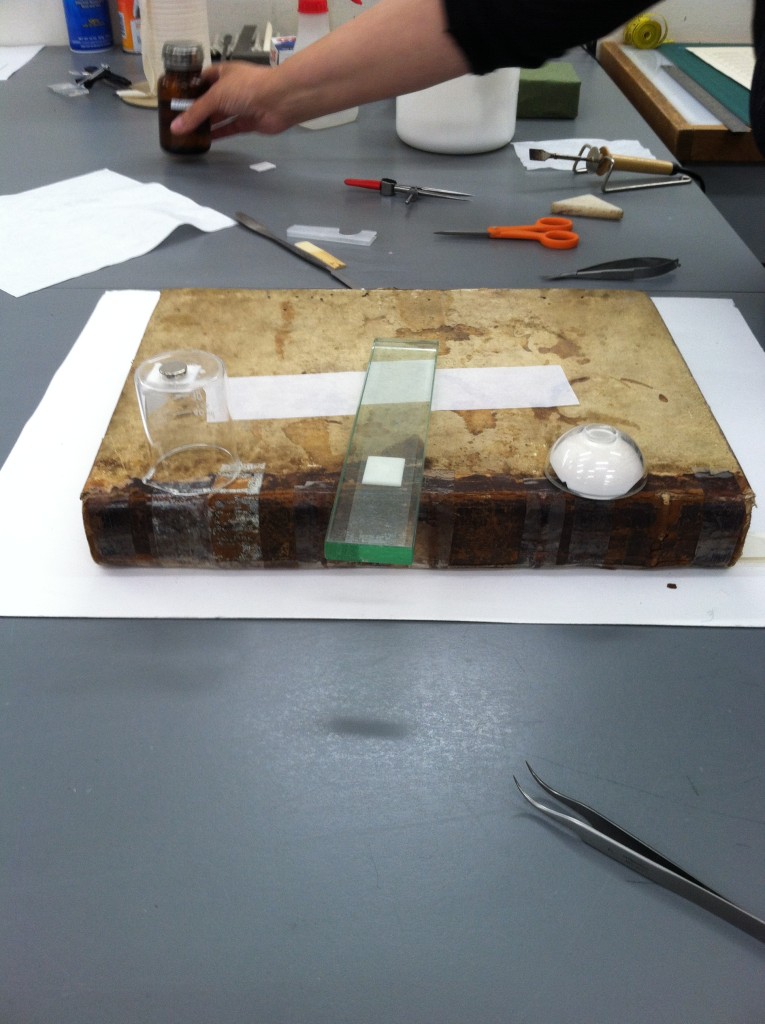

If a book is expected to see heavy use, the treatment focus is going to put on making the binding functional and able to withstand handling. Often times, this means rebacking the binding in cloth, leather, or tissue, and treating the pages so that they can be flipped through without crumbling to pieces. Circulating collections conservation labs see this work most often, performing rebacks as if they were as second nature as brushing ones teeth. Special collections conservation labs see this less frequently, but if a binding is special enough, it might require a full treatment: disbinding, washing and sizing, and either repairing the original binding or giving it something shiny and new. The treatment that I described in my previous post, where a loss was filled in the front cover of a wooden boards binding, was done because the volume was expected to see use and having a complete front cover would prevent a significant amount of damage to occur in its handling.

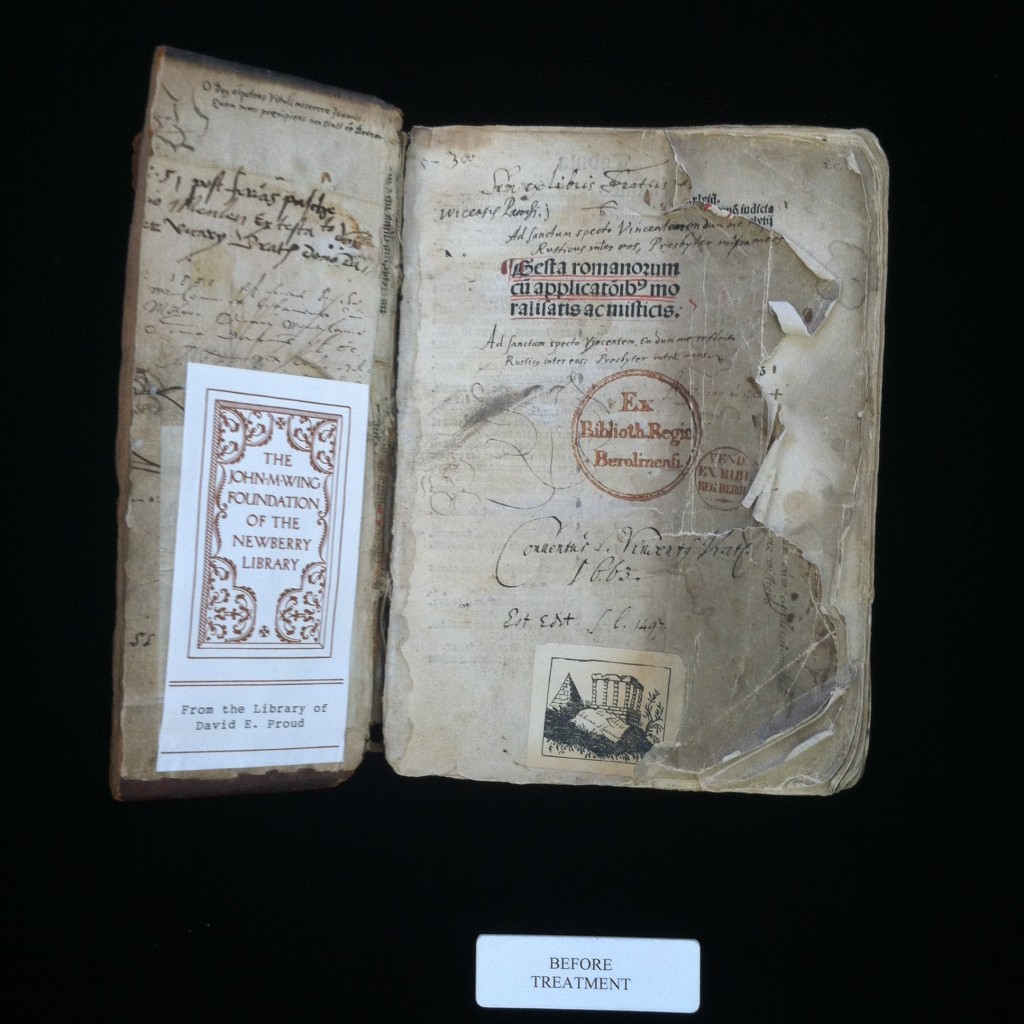

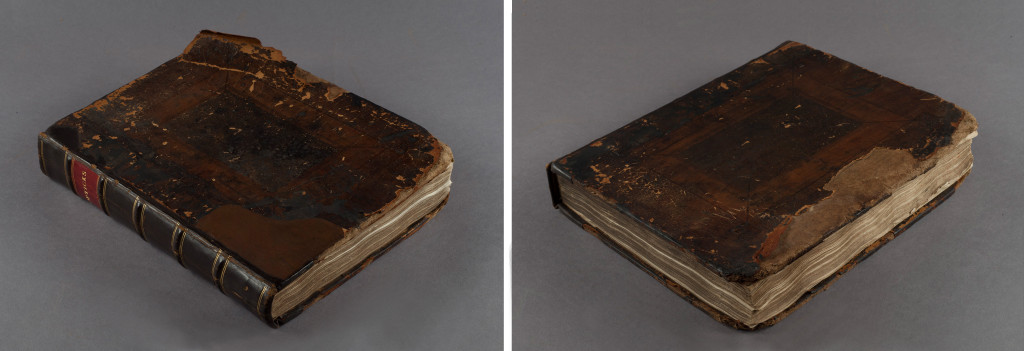

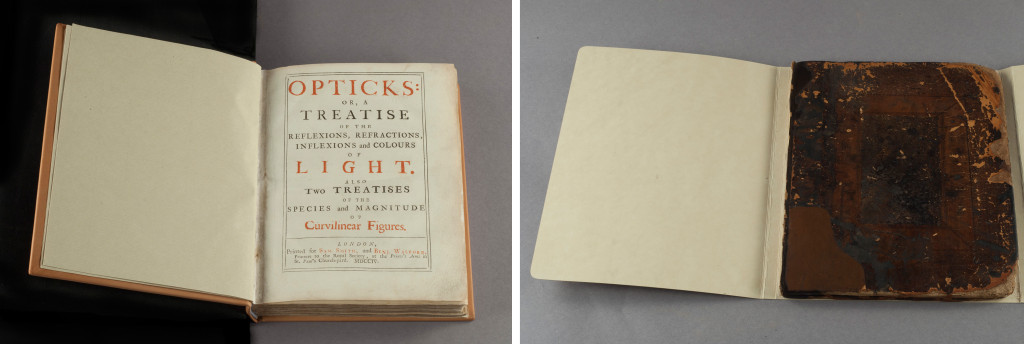

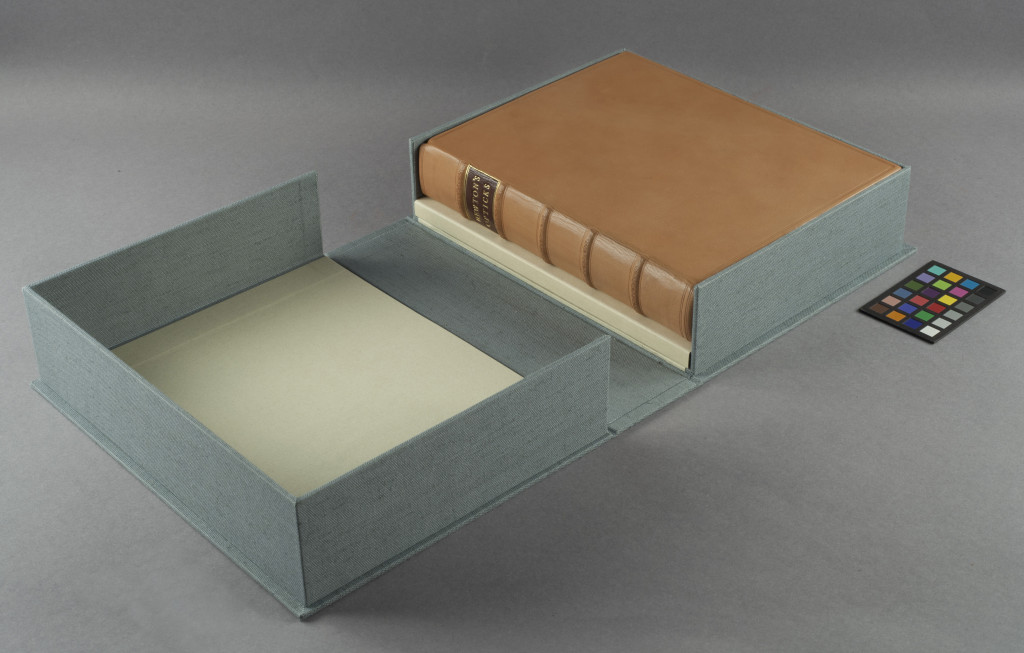

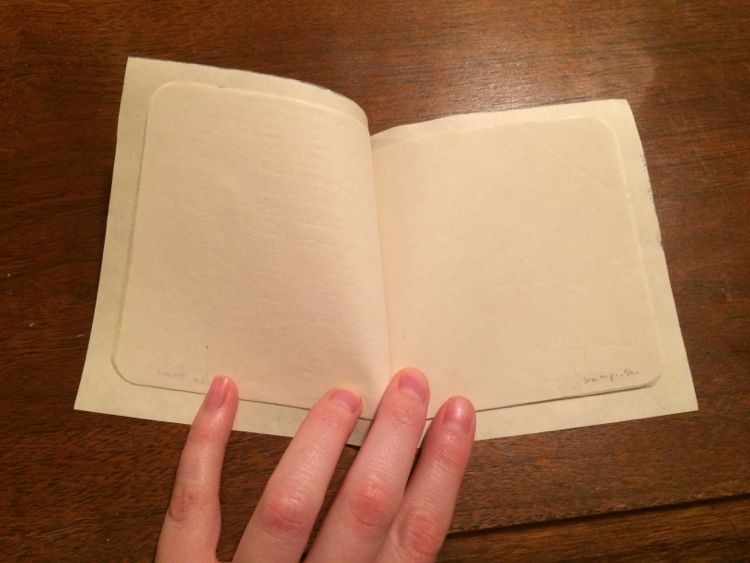

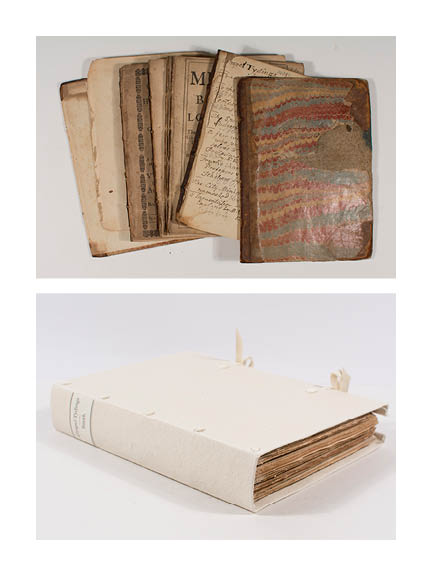

The binding to the left was rare, and as a result likely to be requested by researchers. The above image was before treatment, and any handling would clearly be difficult as the binding had essentially been lost, save for the covers. The volume was treated by washing and sizing the pages, making them softer and easier to handle, mending and guarding, and putting the text into a limp paper case, which opens easily and protects the pages within.

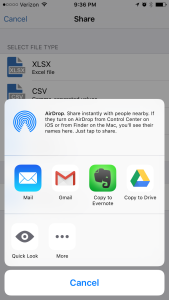

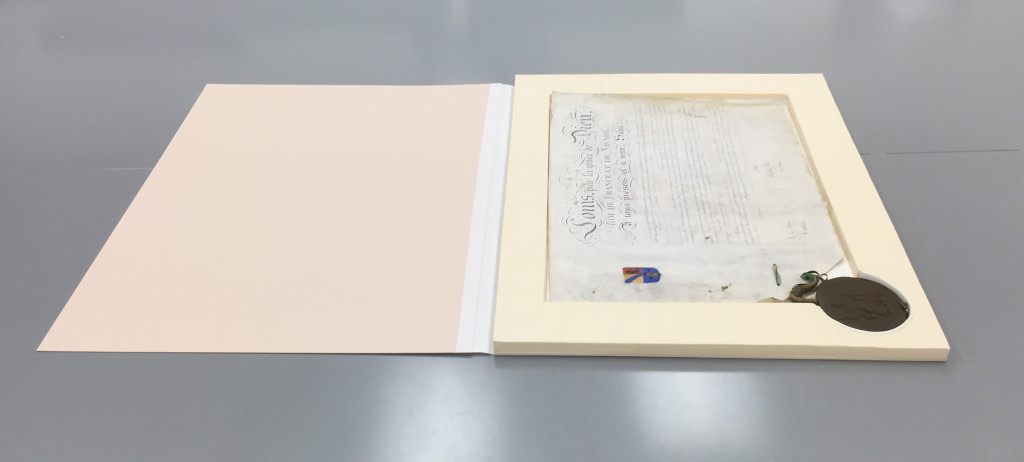

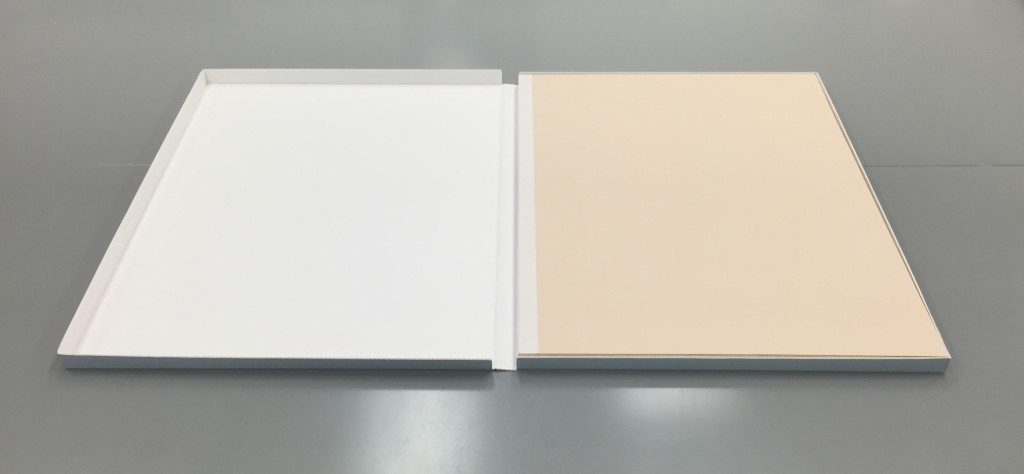

Exhibition:

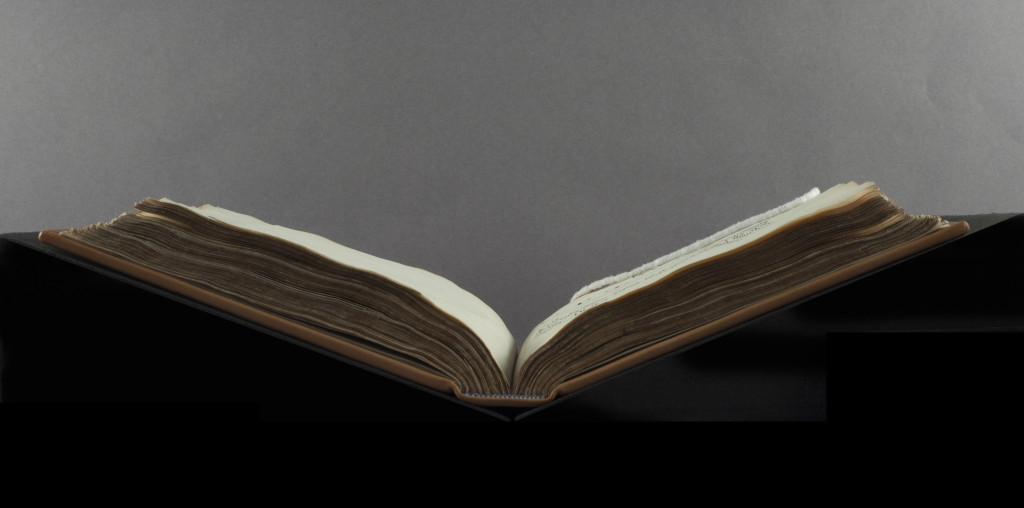

When a book is slated to go into exhibition, this typically means that it is going to sit in a case, opened to one angle for at least a couple of weeks. In this case, it is not so much necessary to treat the entire binding as it is to make sure that the binding will be stable when it is on display. Making sure that the binding doesn’t open past where it is comfortable by fitting a cradle to it is paramount. Treating the pages that it will be opened to, for handling and aesthetic purposes, is also important. There are some great photos here from the Folger Shakespeare Library’s 2015 three-day symposium on book cradles for exhibition.

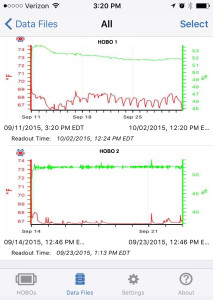

Digitization:

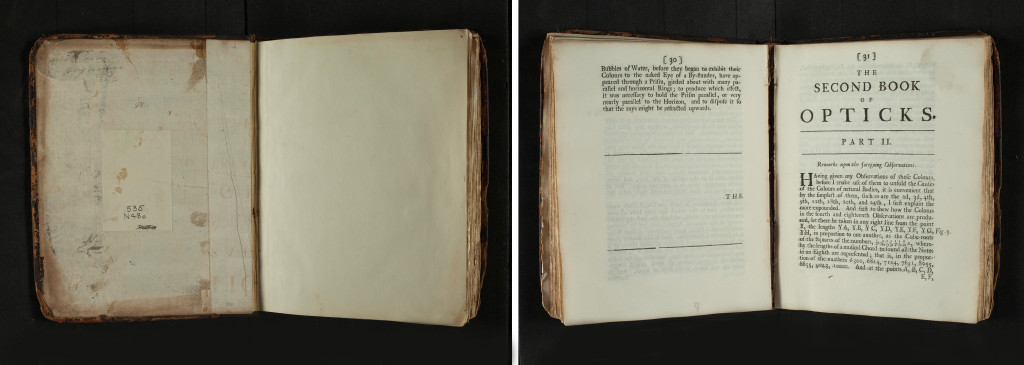

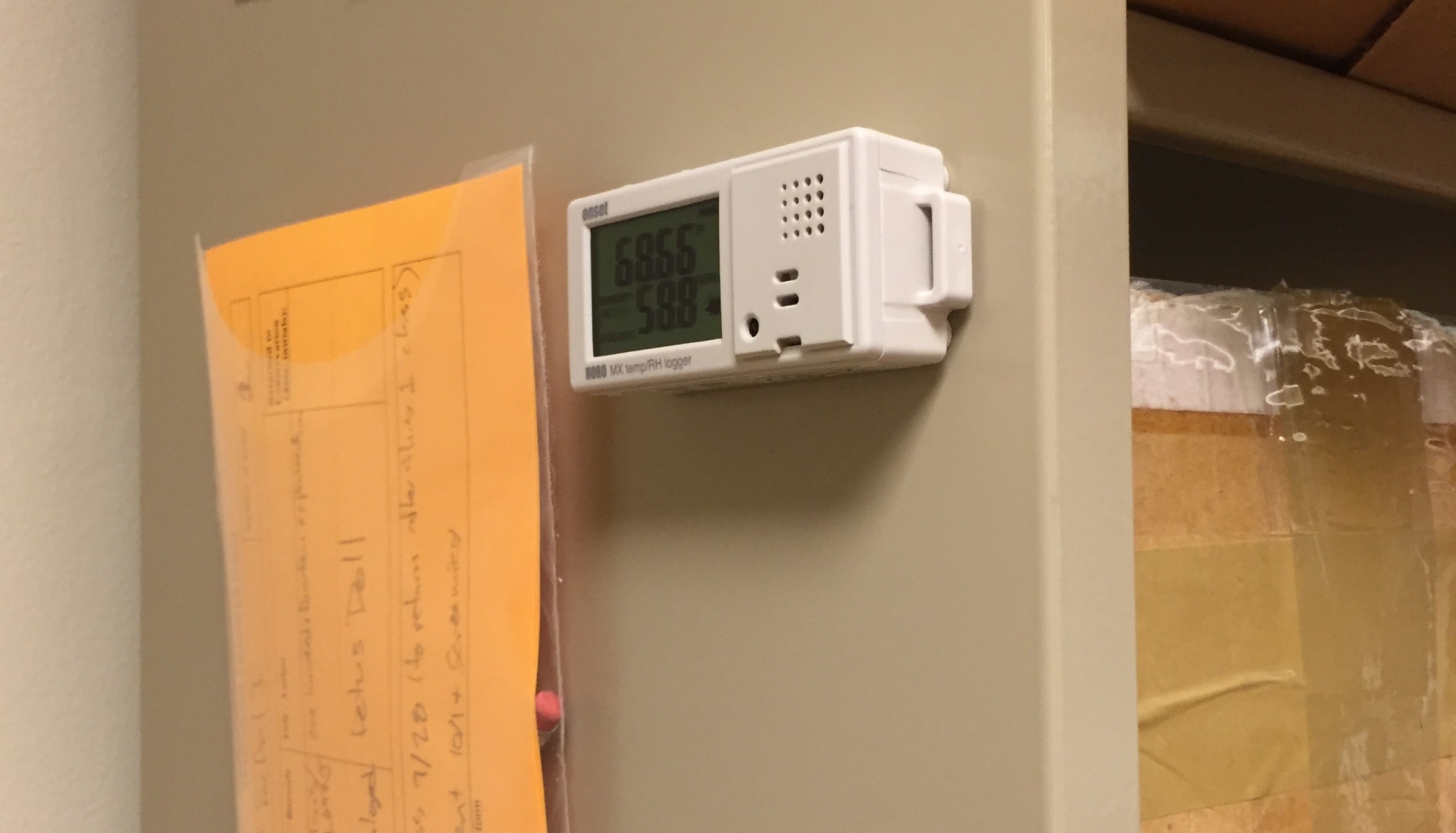

In the short time I’ve spent working in this field, digitization has quickly emerged as the most common reason for treating a volume. Initially, I saw digitization as something that might eventually make conservation work unnecessary. Often the work that is done on an object slated for digitization is quick, with the goal of stabilizing the volume so that it can be handled by the photographer. If something is being put online, presumably where most people will access it, why spend time and money conserving the actual object? However, I hope that digital access will instead serve to peak interest in physical books, resulting in a need to spend more time conserving the bindings so that they can be used. Increased availability of collections will hopefully result in more people being aware of the books that are available to researchers, and after finding them online will want to see them in person. Because digitization is such a new component to conservation, only time will tell how it will affect treatment decision-making.

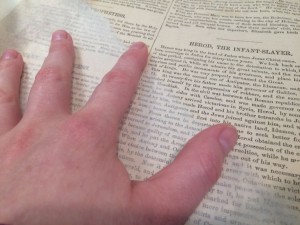

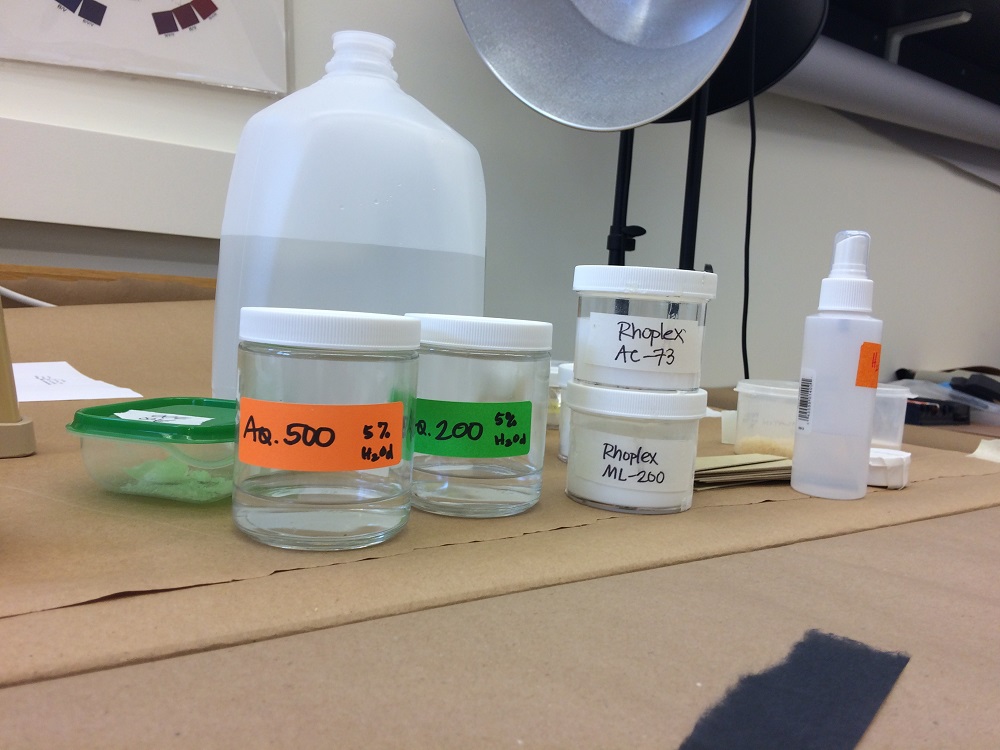

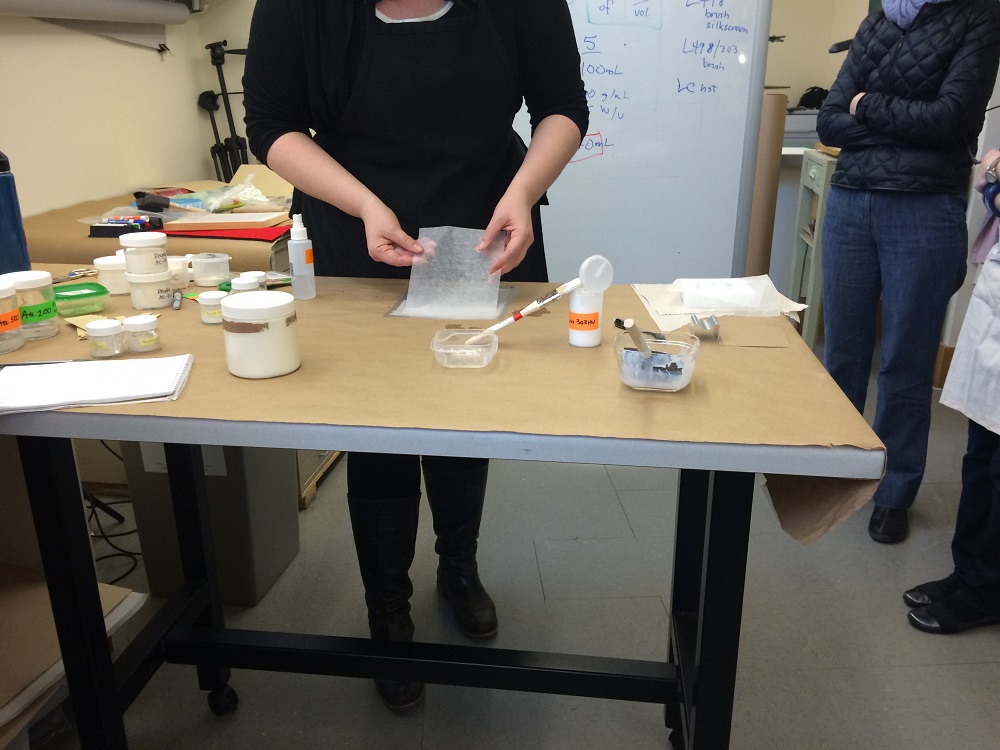

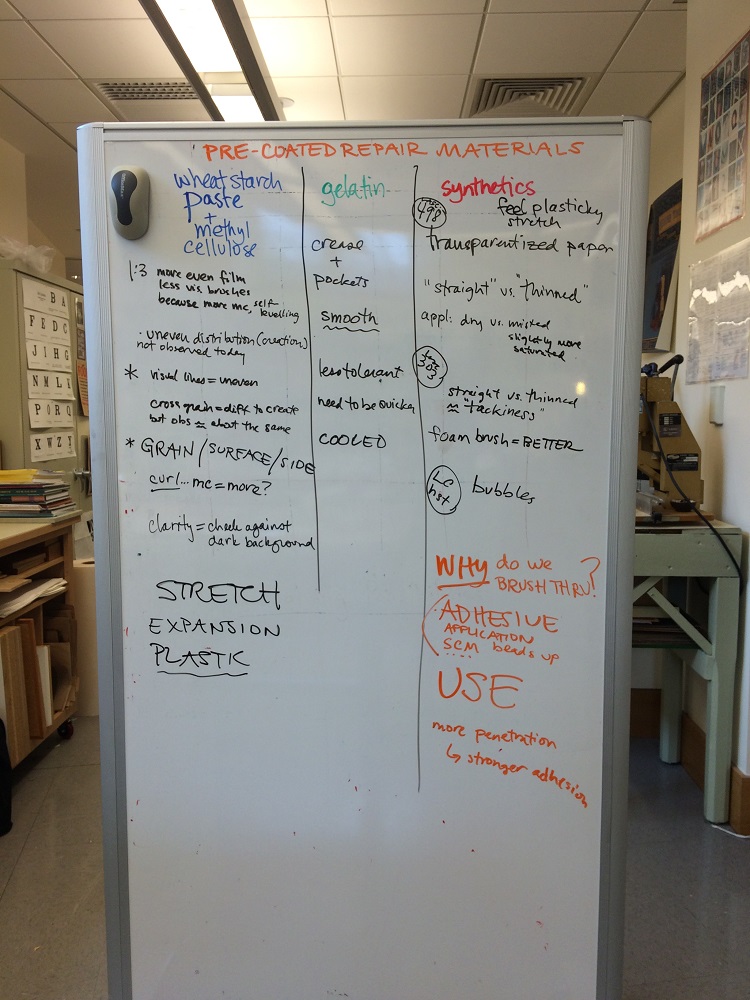

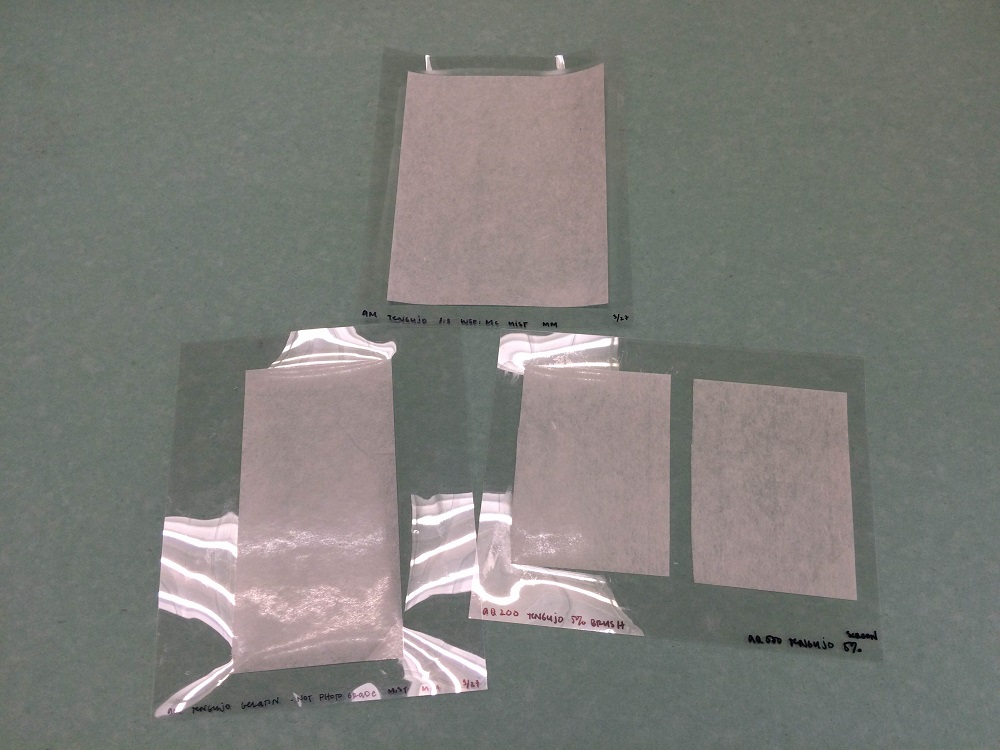

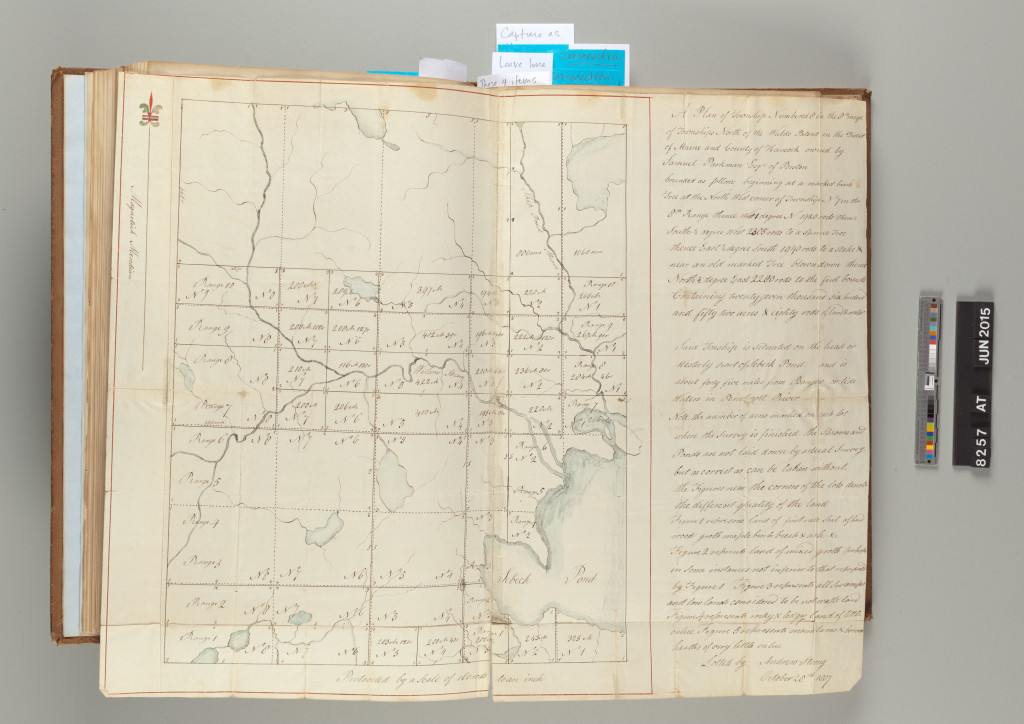

This book was being digitized, and so I used re-moistenable tissue for quick, in-situ repairs of these map folds.

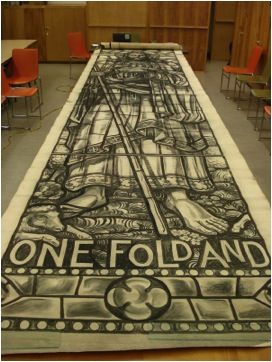

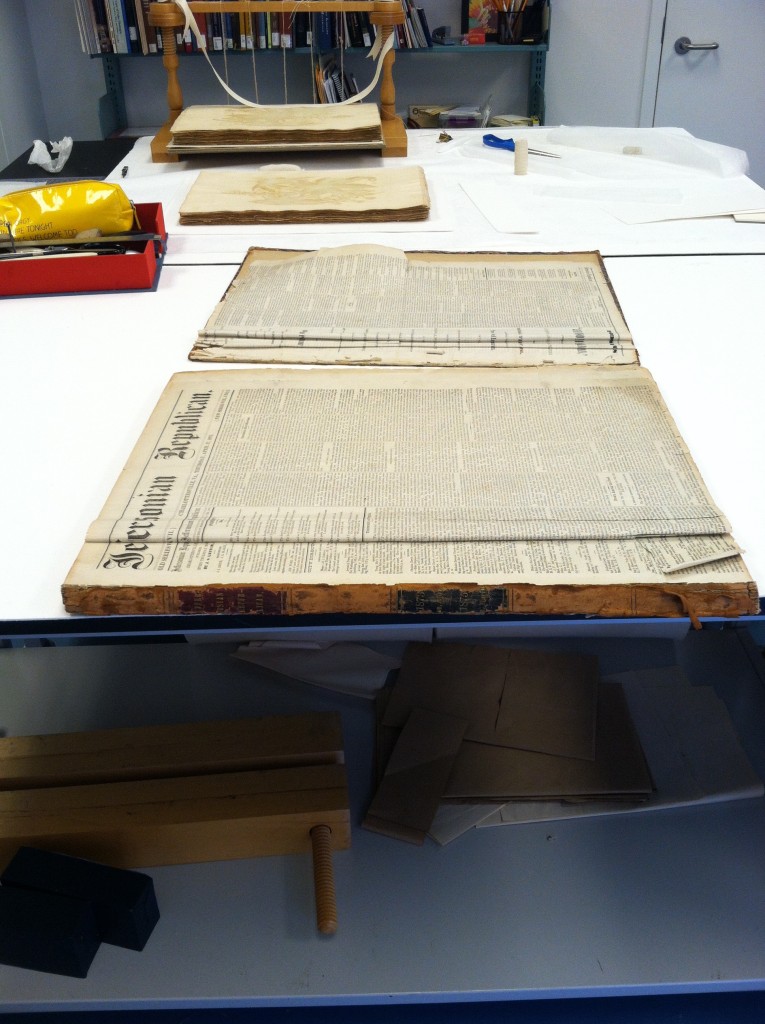

Imaging was also the goal of this bound volume of 19th century newspapers. The papers were disbound and mended, so that they could be imaged flat, and never rebound.